The decision to visit Palermo, the capital of the Italian island of Sicily, was as spontaneous as a change in the wind. Yet, this totally unplanned move turned out to be one of the best trips I have ever taken. I fell in love with the city’s gorgeous monuments, bustling street life, and tantalizing aromas of colorful street markets.

Read the story and see if Palermo would be also your “cup of tea.”

- How I Ended Up in Palermo

- Local Cultural Context: Things to be Aware

- Salt, Sugar and Spleen: Eating Your Way Through Palermo

- An Architectural Feast Where East Meets West

- Beyond Tourist Sights: Fun Things to See and Do in Palermo

- A Day of Ancient Temples and Wild Hot Springs

How I Ended Up in Palermo

In January 2026, I was exploring Naples, a city which can be described as equally “gorgeous, romantic, and adventurous.”

One day, I was having lunch at the trattoria Fratelli Frena, an excellent place to try traditional Gnocchi alla Sorentina coupled with a rustic local Aglianico wine.

The young couple sitting at the next table were discussing their upcoming trip from Naples to Sicily by TRAIN. Mind you: Sicily is an island, and I had visited it previously by ferry boat and plane, but I had never heard about a train connecting it with the mainland.

Take a look where Naples and Sicily are.

As it turned out, there is indeed a direct train between Naples and Palermo which crosses the Tyrrhenian Sea while tucked inside the belly of a ferry boat. Further, there were two options: an overnight train and one leaving Naples at 9.40 am and arriving in Palermo at 7.10 pm.

The idea of visiting Sicily again via a comfortable train-ride and enjoying the coastal scenery was very appealing. I booked a ticket (about 50 Euro / US55$), and left Naples the next morning.

The seats in second class were very comfortable: spacious, reclining, and equipped with tables and power outlets.

Somewhat surprisingly, the train was merely 30% full, and my only companion in the four-seat compartment was an Italian lady with a cute little dog.

The train arrived perfectly on time, and I set off on foot to my lodgings. As I walked the streets, I was amazed at how festive and alive Palermo looked despite the fact that it was a regular mid-week evening.

But then it occurred to me that Sicily is still a very religious (Catholic) part of Italy, and people here were celebrating the approaching (January 6) Feast of Epiphany. Also known as Three Kings’ Day, it is a Christian holiday that celebrates the “revelation” of Jesus Christ to the world.

My “home away from home” in Palermo was a guesthouse called “Cattedrale Central Rooms,” and, as the name suggests, it was strategically positioned very close to the city’s main landmark, the Cathedral of Palermo.

Fast forward, Cattedrale Central Rooms turned out to be an excellent choice: right in the historic center, and yet on a quiet side-street.

The en-suite room at Cattedrale Central Rooms exceeded my expectations: it was spacious, with all modern amenities and a small balcony. But the most enjoyable part of staying here was the guesthouse’s manager, a very welcoming and always smiling fellow named Giovanni. Born and raised in Palermo, he gave me tons of advice on the best ways to explore his hometown.

Each evening, Giovanni would ask what type of pastries I would like for breakfast, and each morning these pastries were brought straight from the local bakery and served with strong, aromatic coffee.

I stayed in Palermo for three days, and this short “trip on a whim” turned into one of my best travel experiences. The Sicilian capital welcomed me with an amazing blend of grand architecture, vibrant street life, bustling markets, and divine culinary adventures, all set against a backdrop of interesting local customs and traditions.

Local Cultural Context: Thing to Be Aware

In order to fully appreciate a visit to Palermo, it is very helpful to be aware of a few basic things about Sicily’s heritage, traditions, and customs.

Let’s start with the fact that Sicily was one of the most frequently conquered regions in human history. From early days of antiquity under Phoenician and Greek influence, it changed hands to the Roman Empire, and then passed through Byzantine, Arab, Norman, and Spanish rule. This constant shifting of dominant powers ended only in 1860 with the unification of Italy into a single kingdom.

This multi-layered cultural heritage is visible today in many aspects: Sicilian architecture, food, customs, and much more. Take, for instance, the so-called “Arab-Norman” architecture, a unique “melting pot” style that emerged in the 12th century. It was a rare moment in human history where Norman conquerors, Arab craftsmen, and Byzantine artists collaborated to create buildings that blended their three distinct cultures.

In Palermo, a striking example of Arab-Norman architecture is San Cataldo Church. Its massive Norman (Romanesque) walls are crowned with Arab (Islamic) red hemispherical domes.

Even long before the Arabs and Normans came to Sicily, the island was already a centerpiece of the ancient Greek-Roman world. Witnessing this fact, the Syracuse Cathedral is a perfect example of the “sandwich of history.”

Indeed, the current Christian church was built around the massive 5th-century BC Greek Temple of Athena. Inside, you will see the original Doric columns embedded in the Cathedral’s walls.

If you look at a Sicilian menu, you aren’t just seeing Italian food; you are seeing a timeline of invasions. For instance, the Sicilian town of Modica is famous for artisanal chocolate. It was thanks to Spanish rulers, who brought ingredients and technology from South America to Sicily resulting in this unique Aztec-style cold-processed chocolate which is very distinct from other European chocolates.

History aside, Sicily remains one of the most traditional and conservative parts of Italy. Family here is not just a social unit, but the fundamental structure of life. It is still common for adult children to live at home until marriage. Even after moving out, the daily involvement of parents (especially the Mamma) in their children’s lives is significant.

Overall, there is a much greater emphasis on collective family reputation and mutual support rather than individual privacy. Here is a great book which gives many insights into traditional Sicilian living through the eyes of a foreigner.

Similarly, Sicily continues to maintain a deeply rooted Catholic identity. Every town or village has a patron saint whose feast day is celebrated with massive processions, fireworks, and centuries-old rituals. The patron saint of Palermo is St. Rosalia, and the Festino di Santa Rosalia is the most important festival in the city, celebrated each July.

Keep in mind, “conservative” in Sicily isn’t about politics, but rather about preservation. Because the island was conquered by so many foreign rulers and powers, Sicilians have historically been wary of “outsiders” and new systems. This has led to a culture that clings to what it knows—its land, its recipes, and its customs.

Finally, there is, probably, one thing which comes to your mind when Sicily is mentioned: the Sicilian Mafia, known as Cosa Nostra (“Our Thing”). What most people, however, do not know is that the mafia emerged in the 19th century not as a crime organization but as a collection of private guards and “mediators” who filled the power vacuum left by a weak Italian state.

Fast forward, through most of the 20th century, the mafia indeed dominated Sicily’s economy via business protection rackets and massive construction projects. You have probably heard about or watched “Godfather,” the iconic movie which won numerous Oscars.

Most of the movie takes place in New York City, but the origins of Corleone “mafia” family were in Sicily, and midway through the film Michael Corleone is forced to flee the U.S. hiding in Sicily for several months. While the cinematographic Corleone family was fictional, the Corleonesi clan in Sicily was very real and far more terrifying than their on-screen namesakes.

In the film, Vito Corleone is portrayed as a “man of honor” who values tradition and family, refuses to deal in drugs, and prefers diplomacy over violence. In reality, the Corleonesi who rose to power in the 1970s broke every traditional “rule” of the mafia. They formed a faction that launched a “Great Mafia War” in the 1980s, killing over 1,000 rivals and innocent civilians to take absolute control of the heroin trade and the island as a whole..

The mafia’s influence was severely weakened in the late 20th century following a brutal war against the state and the subsequent arrests of top bosses. Yet, today, Cosa Nostra remains active but faces intense pressure from Italian law enforcement and grassroots anti-mafia movements. In Palermo, you will see many shops and restaurants bearing this logo.

This logo indicates that this business is part of Addiopizzo association, which translates to “Goodbye Protection Money.” Founded in 2004, it is a grassroots movement of business owners and consumers who joined forces to fight the Mafia’s economic stranglehold on Sicily. Addiopizzo’s logo symbolizes the breaking of the Mafia’s chain of command.

Salt, Sugar and Spleen: Eating Your Way Through Palermo

Why this “Holy Trinity?” Well, “salt” is for the street food and snacks, “sugar” is for Sicilian world-acclaimed pastries, and “spleen” is for some more “adventurous” items of local gastronomy. Overall, the best definition of Sicilian and Palermo cuisine is “comfort food:” simple, but highly satisfying.

So, what is a “must try” while here? Perhaps the two most iconic and advertised items are “arancine” and “cannoli.”

Arancine are big, deep-fried rice balls traditionally filled with savory ingredients like meat ragù, mozzarella, and peas. The name translates to “little oranges,” a nod to the golden crust and vibrant orange hue of the saffron-infused rice.

Arancine are commonly served as street food, but in Palermo you can also find a few places which offer much more sophisticated versions of this dish. One of them is cafe “Arancine d’Autore.”

This place serves about two dozen various “arancine,” including vegan options, sweet (dessert) versions, arancine filled with seafood or mushrooms, and even baked (rather than deep-fried) arancine.

What about “cannoli?” These are pastries with a tube-shaped shell of fried dough that is light and crunchy. The shells are filled with a sweet, creamy filling made from fresh ricotta cheese. To properly finish this delicacy, the outside ends are often covered with pistachios, mini chocolate chips, or candied orange peel.

Where are the “best cannoli” in Palermo? As you can guess, the local residents have a significant variety of opinions about the best spots. In my experience, cannoli offered by street-vendors were often as good as the ones served in more sophisticated settings like cafes and restaurants.

You are probably still curious why I mentioned “spleen” while describing food in Palermo. The answer is Pane con la Milza (or Pani câ Mèusa), a sandwich made of boiled and fried organ meats. The base of the sandwich is a soft, round, sesame-seeded bun called vastedda. The filling consists of three parts of the calf: spleen (“milza”), lungs and trachea.

The meats are first boiled and then sliced into thin strips. When you order, the vendor takes a handful of the meats and flashes it in a large, copper vat filled with hot lard (strutto) to make it tender and intensely flavorful.

Pane con la Milza is not just a hallmark of cucina povera (“peasant cooking” or “kitchen of the poor”), but an interesting blend of religious history and poverty-driven innovation. The dish dates back to the 11th century, when Palermo had a large Jewish community. Many Jews were butchers, but their faith forbade accepting money for the act of slaughtering animals. Instead, they were often compensated with the offal (the internal organs). To turn these “scraps” into a livelihood, they boiled and fried these meats, and sold them as sandwiches to the local Christian population.

What else to “savor” in Palermo? I was there for only three days, and clearly my gastronomic experiences are far from comprehensive. But here are a few things which I liked. One was “panelle,” fritters made from a batter of chickpea flour, water, and parsley. Everything is cooked into a thick paste before being thinly sliced and deep-fried. The golden squares are finished with a squeeze of fresh lemon and a pinch of salt.

Somewhat similar and equally enjoyable were “crocche” (or “cazzilli“), smooth potato croquettes flavored with fresh parsley or mint and deep-fried until they develop a thin, golden crust. Sometimes, crocche are served together with panelle inside a soft sesame roll to create the ultimate carb-filled sandwich.

On the sweet side, and even more than cannoli, I indulged into “genovesi,” soft, circular pastries made from a special dough (pasta frolla) that includes durum wheat flour for a distinct texture. Genovesi are filled with a thick, lemon-scented ricotta cream and are best served warm.

Why the name “genovesi” which suggests origins in Genoa (Liguria region of Italy)? The most popular theory is that their shape resembles the hats of Genoese sailors who traded in the nearby port of Trapani centuries ago. Others believe they were inspired by a similar Ligurian biscuit called “panarella,” which was adapted by Sicilian nuns. One way or the other, I started each morning with two warm “genovesi” accompanied by a cup of invigoratingly aromatic coffee.

Gastronomy in Sicily and Palermo is rich in various meat-based dishes, but as a non-meat eater, I was more interested in fish and seafood. Being a coastal city, Palermo is also a good destination for lovers of various “frutti di mare” (fruits of the sea).

I am not going to describe all local ways of serving fish and shellfish, but will give a very simple advice: go to one of Palermo’s street markets (“Ballaro” is the biggest) and try various already prepared dishes offered there by the tons of food stalls.

Yet, one fish delicacy that you probably won’t find in the street markets is smoked swordfish. While swordfish is prepared in countless ways across the island – grilled, braised, or rolled and stuffed (“involtini”) – the smoked version is the crown of the Sicilian Antipasto di Mare (seafood appetizer platter).

Often garnished with pink peppercorns and thin slices of fennel or Sicilian blood oranges, smoked swordfish is sliced paper-thin and served raw, much like salmon carpaccio. But because swordfish is meaty and lean, It has a much milder, and cleaner taste than smoked salmon.

After getting a picture of “what to eat in Palermo,” you are likely to ask: “Where are the best places to eat?” Problem is that besides the overall quality of food, “best” has very a different meaning for various people, including affordable price, ambiance of the setting, size of the portions, and much more. The good news is that Palermo has tons of restaurants, cafes, and bars which should satisfy any wallet or palate. I will simply mention a few options.

A truly unique dining setting in Palermo is the street markets, with Ballaro being the largest one. Most of them not only offer various prepared dishes, but also have tables and chairs so you can eat comfortably, almost like in an outdoor cafe. In fact, eating at a market is more than just exploring local cuisine. It is an adventure for all the senses, where the bustling street life, vibrant colors, and intoxicating aromas create an atmosphere that makes every bite feel like a discovery.

An additional bonus of a meal at the market is that – instead of ordering a full-size portion – you can try small plates of different foods. And to make things even easier, many stalls have a flat price of 5 Euro / US6$ for a plate of any dish.

Even better, it is also common to be offered free samples so you can better make your choices.

The only limitation of dining at street markets is that they close relatively early: typically by 8 pm. Afterwards, for a variety of restaurants and cafes staying open late into the night my recommendation is to walk along Via Maqueda – it is lined with places to eat for all tastes and budgets.

If you want a more authentic and “of the beaten path” dining experience, here are two interesting spots. For a local vibe and home-style meals, go to Antica Focacceria San Francesco. It is more than just a restaurant; it is a living monument to Sicilian culinary history. Located right across from the Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi, it has been serving traditional food since 1832.

The Focacceria began in a former chapel of a 17th-century noble palace. Its interior is a cool example of the Art Nouveau style with cast-iron tables and wooden furnishings. Among the famous figures who ate here were personalities like Giuseppe Garibaldi, Luigi Pirandello, and Leonardo Sciascia.

Despite its historic fame, the Focacceria remains a fairly humble cafeteria-style establishment. I went there twice and – to my surprise – did not meet any tourists. All who ate there looked like truly local “Palermitani.”

The daily changing menu is written on a big chalkboard, but you can also come to the glass-covered counter and select from the displayed dishes. You will find here all the iconic Palermo foods which I described earlier: Arancine, Panelle, Cazzilli, Pane ca Meusa, Cannoli, and much more.

One of my personal “food discoveries” at Antica Focacceria was “Sfincione”, an incredibly flavorful, thick, spongy pizza topped with tomato sauce, onions, anchovies, and oregano.

Another recommendation for an interesting place to eat in Palermo is Bocum, an artisanal bakery and cafe. Unlike Antica Focacceria which is keen on preserving old cooking traditions, Bocum offers a contemporary take on Sicilian foods.

When it comes to breads and pastries, the bakery takes inspiration from French boulangeries but uses local ingredients and ancient Sicilian grains like Tumminia, Perciasacchi, and Maiorca.

Beyond sweets and breads, at Bocum, you will find a number of other food options: pizza in teglia (pan pizza), various stuffed focaccias, and “rosticceria” items.

Local folks told me that Bocum is also known for hosting jazz and piano performances: so, I guess, I need to come back and check it out.

An Architectural Feast Where East Meets West

Sicily’s status as a cultural crossroads is epitomized in a remarkable fusion of architecture styles, with Palermo being a prime location to explore this blend of epochs and traditions.

First, it is famous for its Arab-Norman buildings—a mix of Byzantine, Islamic, and Western influences. Palermo is one of the few places on earth where you can see Islamic Fatimid arches, Byzantine gold mosaics, and Latin floor plans in a single building like the Palatine Chapel.

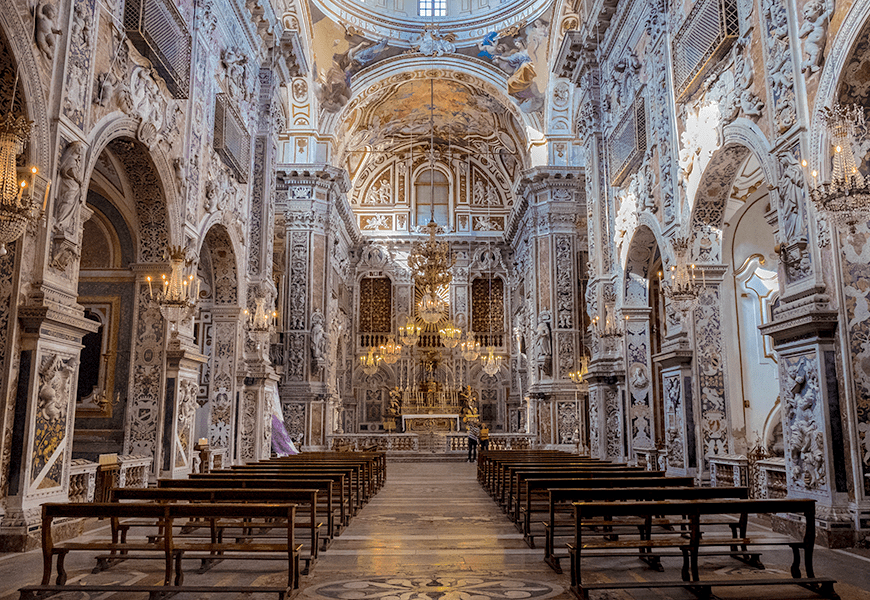

Second, Palermo is world-renowned for “Sicilian Baroque” characterized by concave and convex facades, grinning stone masks, wrought-iron balconies, ornate stucco work, and “marmo mischio” (mixed marble) interiors – all creating a sense of movement, elegance, and splendor.

Finally, walking through central Palermo, you will also encounter Neoclassical grandeur. In fact, during the late 18th and 19th centuries, Neoclassicism gave Palermo some of its most iconic public landmarks, hinting that the city had became a modern, European capital.

I am not going to write a guide to Palermo’s architectural wonders, but will simply mention a few places which are truly “must sees.” The first on the list is Quattro Canti, an octagonal Baroque square which is the symbolic heart of the city.

Each of the four curved facades forming the square is a sculptural masterpiece divided into three levels which represent the seasons, the four Spanish kings of Sicily, and the four female patron saints of the city.

Quattro Canti translates into “Four Songs,” indicating that this intersection of Via Maqueda and Corso Vittorio Emanuele used to split the historic center into four distinct quarters (mandamenti).

The square is also known as Il Teatro del Sole – The Theater of the Sun. Why? Because it is designed so that at least one of the facades is illuminated by sunlight at all times throughout the day. I also recommend coming here at night when all the walls and and sculptures are colorfully lit by a bright illumination.

After Quatro Canti, go to Palermo Cathedral which is probably the best example of Palermo’s “architectural feast.” It combines the scale of a fortress, the ornamental details of a mosque, and the majestic dome of a Neoclassical basilica. Make sure to give yourself at least an hour, because in terms of both its size and things to explore, it is almost like a “city within the city.”

Before venturing inside, go to the eastern facade, which is the most historically significant part of the entire structure. While the southern – main entrance – side underwent several renovations, the eastern wall remains an authentic representation of the original Arab-Norman style that defined Sicily’s “Golden Age” in the 12th century.

Made of lava stones, the three curved sections of the eastern wall are a mesmerizing fusion of Norman structure (fortress-like build) and Arabic decoration (interlacing arches and stone patterns). The interlacing (crossing over each other) patterns were the hallmark of North African architecture, and the Norman kings adopted them to show that they were cosmopolitan rulers.

After exploring the “origins,” go to the south side and the main entrance. Both the Porch (entrance) and the soaring towers in the background were built in the 15th century in the Catalan Gothic style.

But the time journey is not finished yet. Before the foundation of the current Cathedral in 1185, this place was first occupied by an early Christian basilica (4th-9th centuries), and then, after the Arabic conquest (831), it was converted into a mosque during the 9th-11th centuries.

Walk to the entrance and look at the left column: there is an original Quranic inscription carved into it. This is a remnant from when the site was a mosque during the epoch of the Islamic Emirate of Sicily (9th-11th centuries).

Finally, before stepping inside, take a look at the huge dome crowning the Cathedral. This is the most recent (late 18th century) Neoclassical addition.

After entering the Cathedral, the first thought is about striking contrast between the building’s ornate exterior and the “calming” Neoclassical interior, a result of the redesign in the late 18th century. After the “chaos” of Arab-Norman and Gothic styles outside, the inside feels much more restrained and orderly.

In the Cathedral, you will find some of Sicily’s most significant historical treasures. One of them is a richly decorated chapel which holds the remains of Palermo’s patron saint, Santa Rosalia. It is also nicknamed the “silver chapel” because its centerpiece is a massive, solid silver altar.

As for Santa Rosalia, according to tradition, she saved the city from a devastating plague in 1624. Born into a noble family in the 12th century, she has chosen to live as a hermit on Monte Pellegrino overlooking Palermo. Centuries after her death, she appeared to a local man during a plague outbreak and led him to her remains in a cave. When her bones were carried in a procession through the city, the plague miraculously ceased.

A truly interesting personality buried in the Cathedral is Frederic II (1194-1250), the most “eccentric” king of Sicily. Known as Stupor Mundi (the Wonder of the World), he was a man far ahead of his era, blending intellectual curiosity with a flair for dramatic political moves.

Frederick was obsessed with the natural world, and wrote an exhaustive book on falconry (De Arte Venandi cum Avibus) that is still respected by ornithologists. Legend says he conducted “experiments” to see if a soul leaves the body at death. He also transformed his court in Palermo into a cosmopolitan laboratory where Arab, Jewish, and Christian scholars collaborated.

Being a Christian monarch, he yet preferred Muslim soldiers as his private bodyguards because they were loyal only to him and immune to the authority of the Pope. His most remarkable political action was the Sixth Crusade. Instead of fighting with Muslims, he negotiated a treaty with the Sultan of Egypt and regained control of Jerusalem peacefully. But the Pope was furious that Frederick hadn’t shed “infidel” blood and excommunicated him (i.e., expelled him) from the Catholic Church.

Walk through the Cathedral and look at two side chapels with massive porphyry tombs of Frederic II and other Sicilian medieval rulers.

Before leaving the Cathedral, find the Chapel of Madonna Libera Inferni (Madonna who frees from Hell). The marble statue of the Madonna and Jesus was created in 1469 by Francesco Laurana. According to the legend, the sculpture was commissioned for another church in Erice (near Trapani). But when it arrived in Palermo to be transported to its final destination, the citizens were so captivated by its extraordinary beauty that they “kidnapped” the artwork, insisting it remain in the Cathedral.

The name “Libera Inferni” (Free from Hell) was bestowed in 1576 by Pope Gregory XIII. He granted a special “privileged altar” status to this chapel, meaning that an indulgence (forgiveness) could be obtained for the souls in Purgatory whenever Mass was celebrated there. So, make sure to say your prayers before heading for your next destination.

After the Cathedral, go to Piazza Bellini to see the Churches of San Cataldo and the Martorana. Sitting right next to each other, they couldn’t possibly be more different in appearance; one austere and Norman, the other a glittering Byzantine masterpiece.

Built atop remnants of the ancient Roman city walls, San Cataldo is the purest surviving example of Arab-Norman architecture in Palermo. It stands out with stark architectural minimalism in a city known for its intricate exteriors and interiors.

Some people are confused by San Cataldo’s three vivid red domes and think it is – or used to be – a mosque. While this is not true, the Arabic/Islamic influence on the church constructed in the 12th century is evident.

Make sure to visit inside, because this is like a time-capsule experience. Unlike many neighboring churches that were heavily modified during the Baroque period, San Cataldo’s interior remains in its original, somber 12th-century state.

Why such unusual austerity? San Cataldo was a personal project of Maio of Bari, the most powerful statesman in the 12th-century Norman Kingdom of Sicily. Serving under King William I, he held the title of Admiral of Admirals, a role equal to a Prime Minister. But his immense influence led to a conspiracy among the other aristocrats, and he was assassinated on the streets of Palermo before San Cataldo was fully finished and the decorative mosaics could be installed.

When walking in San Cataldo, look under your feet. While the walls are bare, the original floor features an elaborate mosaic that blends Roman, Byzantine, and Islamic patterns.

After San Cataldo, go literally “the next door” to the Martorana Church, officially known as Saint Mary ‘dell’Ammiraglio. In stark contrast to the humbleness of San Cataldo, Martorana is famous for its opulent Byzantine mosaics and frescoes.

Similarly to San Cataldo, Martorana Church was constructed in the 12th century by another powerful nobleman, George of Antioch, a Syrian-Christian admiral serving the Norman King Roger II. But unlike assassinated Maio of Bari, Admiral George was able to finish his project.

The entire interior is literally draped in shimmering mosaics, with the vaults being the centerpiece of the church’s decoration and history. They feature an image of Christ Pantocrator in the dome and a scene of King Roger II being crowned directly by Christ, a powerful political statement of the era and clearly a flattering gesture on the part of Admiral George.

Why is the church mostly known as “Martorana” and not under its official full name? “Martorana” comes from Eloisa Martorana, a noblewoman who founded a nearby Benedictine convent in 1194. The church became permanently linked to her name in 1433, when King Alfonso of Aragon granted the building to the nuns of the adjacent convent.

By the way, for many people, “Martorana” will evoke not a sacred but a culinary association with the Sicilian “Frutta di Martorana,” the marzipan that is shaped to look like real fruit.

This popular dessert was invented by the nuns of the Martorana convent. Legend says they made and hung almond-paste fruits on the trees to impress a visiting dignitary—either a Pope or Emperor Charles V—because the real fruits were not in season.

One more recommendation about Martorana Church. Even if you are not religious, come here in the evening for the worship service. Today, the building belongs to the Italo-Albanian Catholic Church which maintains the ancient Byzantine rite with prayers being said in archaic Greek or Albanian.

I was lucky to be in Palermo on January 6th, which is the Christian feast of the Epiphany, the Baptism of Jesus Christ. The celebration at Martorana Church was gorgeous, and I could feel the uplifting spirit of the people who came to worship there.

You probably feel tired already from exploring various religious sites of Palermo, but one more “sacred” destination is absolutely a must-visit. This is the 14th century Santa Caterina Monastery which is located right next to the San Cataldo and Martorana Churches. As you will see, there is not one but a number of reasons to explore this place.

First, come to Santa Caterina when you are hungry, because the monastery has an outstanding bakery. Called “I Segreti del Chiostro” (The Secrets of the Cloister), it uses ancient, once-secret recipes of the nuns who lived here until very recently.

People come here for several signature items. The monastery’s cannoli are known for being huge in size and filled with ricotta cream individually for each customer to ensure the shell remains crisp. The bakery is also a place to try some other specialties which would be hard to find anywhere else.

Among these rare items are the cake Trionfo di Gola (Triumph of Gluttony), and the Fedde del Cancelliere (Chancellor’s Buttocks), made with pistachio almond paste and apricot jam. I personally fell in love with Biscotti Ricci, almond based biscuits.

The best thing is that all these treats can be enjoyed in the monastery’s courtyard while listening to the birds and the calming sounds of a fountain. Filled with citrus trees, it has comfortable benches, and chances are great that even after finishing all the sweets, you will be tempted to linger here for a while.

Then go to the monastery’s church. Even after seeing other fine examples of Sicilian Baroque, you still will be overwhelmed with lavish, exuberantly luxurious decorations and fine “intarsia,” an artistic technique where pieces of marble are inlaid into a solid surface to create complex patterns or pictorial scenes.

After admiring the church, take the elevator and then climb the stairs to the monastery’s rooftop. The observation deck here offers best 360-degree views, overlooking monastery’s courtyard, Piazza Pretoria, and Palermo’s historic center.

The final part of the visit to Santa Catarina is the most intimate one. The Dominican nuns left the monastery in 2014, but walking around you still can see and feel how they used to live here. For example, on the second floor, there is a corridor which loops around the entire church with barred windows looking inside the sanctuary. This was the place where nuns used to sit during worship services, because they were not permitted to mix with the general public present in the church.

The rooms of the last three nuns are kept as if they are still here, and these cells are open to visitors. Regrettably, taking pictures is not allowed there for privacy reasons.

Okay, enough religious sites, but let me tell you about three more architectural attractions in Palermo which should be on your itinerary. You cannot visit the city without exploring Piazza Pretoria (Pretoria Square) with the massive Fontana Pretoria, a Renaissance artwork that occupies nearly the entire square.

Featuring 48 statues, the fountain wasn’t originally built for Palermo. It was commissioned in 1554 for a private villa in Florence. When the owner fell into debt, he sold it to the Senate of Palermo. The fountain was dismantled into 644 marble pieces and shipped to Sicily. To make room for its 133-meter/150-yard circumference, several houses were demolished.

Among the locals, this square is known as “Piazza della Vergogna” – the Square of Shame – and there are at least three versions explaining such a name. The first is about chastity. Being much more conservative than the residents of Florence, the Sicilians—and particularly the nuns from the overlooking Monastery of Santa Caterina—were scandalized by the explicit nudity of the statues. Legend says nuns would occasionally sneak out at night to damage or cover the “shameful” parts.

Another theory is about political corruption in the City Hall that borders the square. The exuberant cost of shipping the fountain during a time of famine and poverty led citizens to shout “shame” at the politicians.

Finally, there is also a more modern version for labeling this square with “shame.” One of its corners is occupied by once gorgeous but presently abandoned and dilapidated mansion. Apparently, since the 1950s, a number of families who jointly own the building cannot agree on its future.

It is indeed a shame to slowly kill such a majestic house.

One more tip is: visit the piazza Bellini and the fountain after sunset. They are brightly illuminated, and the marble statues stand out dramatically against the night sky.

The second recommended destination is perfect for a “siesta” and respite: I am talking about Villa Bonanno, a nicely manicured and surprisingly tranquil park right next to Palermo Cathedral. Most people do not know that beneath the park’s lawns lie the remarkably well-preserved remains of Roman patrician houses (domus) dating back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries BC.

The park is home to a good number of sculptures depicting various illustrious Sicilians. The most impressive monument is dedicated to Philip V, a pivotal figure in European history, primarily known as the first Bourbon (i.e., coming from the French dynasty) King of Spain.

I loved the dense groves of tall palms and orange trees, and sat each day under their lush, green canopy while checking emails and making further travel plans.

The final “must see” architectural masterpiece of Palermo is the Teatro Massimo (Massimo Theater). It is the largest (measured by total floor area) opera house in Italy and the third-largest in Europe, which covers an immense 7,730 square meters (over 83,000 square feet) footprint.

With a temple-like facade, the theatre was designed as a grand Neoclassical symbol of the city, reflecting the prestige and power of a newly unified (1861) Kingdom of Italy. Its construction has taken 22 years (1875-1897) with the original architect (Giovan Battista Filippo Basile) dying midway through the project and his son taking over and finalizing the project.

The chances are great that even without visiting Sicily, you actually have seen Teatro Massimo. Indeed, its massive front staircase was used as a setting for the final scenes of Francis Ford Coppola’s iconic mafia trilogy The Godfather Part III.

One day, I walked by the Teatro Massimo at sunset. The fiery flashes across the darkening sky and the theater’s dominating, temple-like presence made me think of ancient Greek Gods at war.

Beyond Tourist Sights: Fun Things to See and Do in Palermo

The best thing you can do in Palermo after seeing all tourist sights is to walk through various neighborhoods outside the “polished” historic center. Go ahead and explore the narrow “vicoli” (alleys) while absorbing the raw flavors and sounds of true Sicilian life.

You will instantly see that “glory and decay” is a defining characteristic of Palermo’s aesthetic. The city still bears the scars of World War II bombings and the following decades of economic neglect, often directly adjacent to noble splendor.

If you like street graffiti – not just some junk but real artistry – Palermo is also an excellent place to enjoy this kind of artwork.

If random wandering through Palermo does not feel like your cup of tea, you can build walking itinerary along the open-air exhibition of the local photographer, Enzo Sellerio. Born in 1924 in Palermo to an Italian father and a Russian mother, Sellerio became an accomplished photographer whose specialty was black-and-white photography depicting various scenes from Sicilian street life.

In 2024, the city of Palermo put together the “Le Vie di Sellerio” (The Lives of Sellerio) exhibition. It consists of twenty of his most iconic photographs which are displayed on the streets and in exact the same locations where they were originally taken. You can use this “Sellerio route” for your stroll through Palermo.

Take your time at each picture, look around, and compare what you see now and what Sellerio’s photo shows.

Here is one of my favorite pictures from this open-air exhibition. Taken in 1954, it is called “The wife of a crank piano player is ironing outdoors.”

By the end of your “walking day,” go to the city’s waterfront. Once a working harbor, it has been transformed into a rather upscale area with promenades, open-air cafes, and sophisticated yachting hubs. Yet, some historic landmarks will transport you instantly back centuries to a time when this shoreline served as Palermo’s primary shield against invaders coming from the sea.

Among the remnants from the distant past, most prominent is “Castello a Mare,” a 9th century fortress and a residence for various rulers. The sprawling, magnificent ruins receive surprisingly few visitors, and I spent nearly one hour there simply watching the sea and reflecting on how many layers of history were witnessed by this place.

For the best views of the Gulf of Palermo, go to “Murra delle Cattive,” a raised promenade which runs above the old city walls and along the seafront.

The name Mura delle Cattive (Walls of the Widows) has an interesting history. The word “cattive” derives from the Latin “captivae,” meaning “captives” or “prisoners.” In the Sicilian dialect, a widow is called a “cattiva” because she was traditionally seen as a captive to her mourning. Back in the day, social norms required widows to dress in black and remain secluded from public life.

And so, in 1823, the Prince of Campofranco built this promenade on top of the 16th-century fortifications as a place reserved for aristocratic widows who could not walk together with the rest of the public along the popular Foro Italico, the sea-level promenade.

Walking along the Mura delle Cattive, I was entirely alone, and it felt like a ‘full immersion’ into the original purpose of the place: to offer seclusion from the world.

My feeling of solitude, however, was suddenly interrupted by the appearance of a huge cruise ship navigating to the harbor. It made me think about the new kind of invaders – thousands of tourists from this cruise – preparing to disembark onto Palermo’s streets.

For a luxurious sunset, go to La Cala, a historic U-shaped harbor. For centuries, this was the heart of the city’s maritime industry, but today it is filled with pleasure boats and private yachts.

As the sun begins to set, the fresh breeze, swaying masts, fast-changing colors of the sky, and colorful waterfront houses create an atmosphere of both nostalgia and hope—a feeling that tomorrow will be even better than the day now fading away.

What else stands out from my short trip to Palermo? Remember, in the introductory section, I wrote about the Sicilian mafia (HERE). The “No Mafia Memorial” in the center of Palermo is an ongoing effort to reflect on the lessons from the past and eliminate whatever is left from organized crime in Sicily.

It is a cultural and learning center with powerful photographic exhibits, multimedia installations, and documents detailing the “Maxi Trial” and the lives of judges Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, who were assassinated by the mafia. And if you are really interested in the subject of Sicilian “Cosa Nostra,” the Memorial also organizes guided tours dedicated to former mafia bosses and those who dared to resist them.

When traveling, exploring the “world of local wines and cheeses” is one of my obsessions. And Sicily has much to offer in both regards. Among the dozen local cheeses I tasted, my favorites were “Pecorino Siciliano Peppato” and “Piacentino Ennese.”

Pecorino Siciliano is the “golden standard” of Pecorino cheese, which is generally mass-produced in Italy. It is made from the raw milk of Sicilian sheep breeds that graze on wild herbs and grasses, giving the cheese a floral and grassy flavor.

While some Pecorinos use ground pepper, the Sicilian version employs whole black peppercorns. They are added when the curds are placed into traditional wicker baskets (fascedde), which leave a distinctive weaving pattern on the rind.

As for Piacentino Ennese, it is also a sheep milk cheese with a rather interesting history. In the 11th century, King Roger the Norman requested local cheesemakers to create a cheese infused with saffron. He believed the precious and expensive spice would act as a natural antidepressant that would cure his wife, Queen Adelasia, of her deep melancholy.

When Piacentino Ennese is made, saffron is added during the process of fermentation, resulting in a vibrant, golden-yellow color and a delicate, floral aroma. Whole black peppercorns are also put into the curd, providing a spicy contrast to the creamy, aromatic base.

Where to buy these and other Sicilian cheeses? You will find abundant choices both in street markets and upscale tourist shops, but for the best price-to-quality ratio, go to the place called “G. Formaggi.” This tiny shop is situated a bit out of the city center and it is open only in the morning.

When you come there, you are likely to see the locals patiently waiting in line. They do so for a good reason: G. Formaggi offers a variety of high-quality cheeses for a very modest price. You can also taste all of them before making a decision to buy.

When it comes to Sicilian wines, each part of the island offers something unique. You can easily spend a couple of weeks exploring local winemaking traditions and sampling countless single-grape and blended wines. But here are two which I found both highly satisfying and, at the same time, offering a very distinct flavor and aroma.

For whites, make sure to try Carricante, the wine made from the grapes that are grown on the volcanic slopes of Mount Etna. These grapes are late ripeners, often hanging on the vine until mid-October. The result is extremely high minerality and a deep, complex aroma. Carricante is also known for transmitting “volcanic expressions;” wine critics often describe its taste as “crushed rocks” or “smoke.”

Among red wines, I fell in love with Frappato. Typically, Sicily is associated with strong, “sun-drenched” and tannic reds like Nero d’Avola, but Frappato is very different. It is prized for its elegance, translucency, and highly aromatic profile.

On the nose, Frappato explodes with aromas of fresh strawberries, raspberries, and sour cherries.

Similar to cheeses, there is no shortage of options in Palermo where you can drink and buy Sicilian wines. Here is one place which I personally enjoyed: it is called Enoteca Picone.

Besides a great selection of local wines, what I liked about Picone Enoteca is that it combines a wine bar, tasting room, and actual wine shop.

Also, while roaming rooms and exploring shelves, I noted that the bar area was occupied by drinking men who definitely looked like locals – always a good sign.

After completing everything described earlier, I still had one more full day in Palermo. I was tempted to simply relax and enjoy another day in town, but then an idea for a short trip emerged: I was heading out to explore ancient temples and soak in wild hot springs.

A Day of Ancient Temples and Wild Hot Springs

I am a big fan of wild hot springs – the ones where you can soak and relax being surrounded by a nice natural setting. HERE is my previous story about exploring hot springs in Idaho. While in Palermo, I learned about Terme Naturali Libere de Segesta (“Free Natural Spa of Segesta”), several open-air hot pools located in the countryside about 70 kilometers / 43 miles southwest of Palermo.

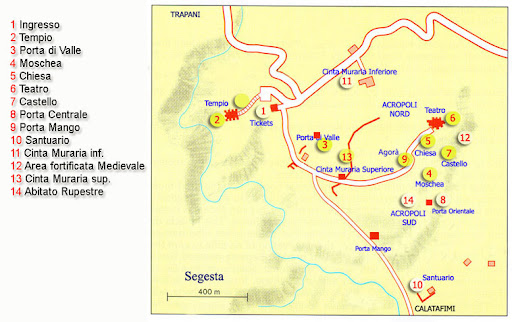

These hot springs are also just a few kilometers away from the Segesta archaeological park. So, I decided to “kill two birds with one stone,” rented a car, and drove to Segesta. Here is a rough map to show where the hot springs and archaeological park are.

Most of the route followed Sicily’s northern coastline, and some of the views were just incredible.

I knew that the weather would worsen as the day progressed and went first to the archaeological park, because exploring various sites requires a good deal of hiking. Even before I arrived at the park’s entrance, the main attraction – the Doric Temple of Segesta – swept prominently into view.

It was one of those “wow” moments when one feels instantly transported millennia back. From afar, the Temple looked absolutely untouched by time, and I felt like the Greek Gods were watching me, a trespasser who was about to step into their ancient world.

After taking pictures from this vantage point, I drove to the park’s entrance, parked the car (you cannot drive within the park), and bought a ticket (16 Euro / US20$). The park is quite widespread with many trails connecting various sites, but I was content with visiting just two highlights: the Temple and the Theatre.

From the ticket office, getting to the Doric Temple was an easy 5-minute walk.

When I approached the Temple, it did not look as perfect as appeared from a distance. Several key elements typical of Greek temples were lacking, including the roof and inner chamber. No surprise about this, though, because archaeologists believe that construction was actually never finished and abandoned around 400 BC due to a war or political shift.

An interesting fact about the Temple of Segesta is that – unlike most Greek-era temples in Sicily – it was built by the Elymians, an indigenous people who adopted Greek architectural styles despite their very distinct cultural background.

I was walking around the Temple, when the wind suddenly picked up, and I clearly heard low, vibrating sounds. Later, I found out that when the air whistles through the structure, the 36 massive columns can act like a giant musical instrument, transforming the Temple into a natural organ.

The hike from the Temple to the Theater and Acropolis is a 1.5 kilometers / 1 mile steep uphill trek. It took about 30 minutes, but as a reward I was offered great views both along the route and at my final destination.

The most special thing about the Theatre of Segesta is its amazing integration with the natural landscape. The semi-circular auditorium is carved into the rock and faces north to provide spectators with a panoramic backdrop of the Mediterrannean and the Sicilian hills. By the way, this ancient structure remains a functional venue, hosting the annual Segesta Theatre Festival.

Regrettably, when I came to the Theater, the weather deteriorated quickly, and dark clouds brought a chilly, drizzling rain. I was done with archaeology and hurried to the car to go to Terme Naturali Libere di Segesta.

Driving from Segesta Archaeological Park to the hot springs is easy: simply put “Natural Spa of Segesta” into Google Maps and in less than 15 minutes you will be there. When I arrived at makeshift parking lot, it became clear that I was not the only one who had the smart idea of enjoying a hot bath on a rainy and chilly day.

Several vans were parked there, displaying license plates from different European countries. It looked like these people were actually using the hot springs as a perfect spot for multi-day camping.

The trail to the hot springs begins at the corner of the parking lot and it is a well-trodden path. The walk is short (10 minutes) and easy, except for one thing: you need to cross the stream.

When I was there (early January), the water was knee-deep and fairly cold. But do not hesitate: remove your shoes, and wade across knowing that just in a couple of minutes you will be properly heated in the giant hot bath.

The main part of the hot springs is a huge, waist-deep hot (40 C / 105 F) pool plus a few adjacent smaller ones. But later I also learned that further along the stream (the one I crossed), you can find a small hot cave that acts as a natural steam room.

What is the source of the hot water? It is rainwater which is absorbed through porous rocks and goes nearly 50 meters deep into the earth, where it meets high-temperature magma. The intense heat creates pressure and pushes – now the mineral-rich – water back up where it emerges through tectonic fractures.

The other typical question is: what are the springs’ mineral contents and health benefits? After interacting with magma, the water comes to the pool rich in sulfur, calcium, and magnesium. It is good for soothing joint and muscle pain (think rheumatism, arthritis, or sciatica) and clearing the respiratory tract (for those with sinusitis, bronchitis, or seasonal allergies). The most powerful impact, however, is a deep muscle relaxation, a relief for people under stress or physical fatigue.

I enjoyed the pools for a couple of hours and drove back to Palermo. After returning the car, I went for a final stroll through the center of the city and to its very heart, the Quatro Canti square. Every evening, various local artists come here and perform for the tourists. It is like a free nightly show.

When I came to Quatro Canti, a young woman was singing on a brightly lit plaza. It was a professional and powerful performance. You can listen to her HERE

The next morning, I headed back to the rail station, a mere 20 minutes walk from my guesthouse. On the the way, I swung, by Villa Bonanno, the green lungs of Palermo. At this early hour, I was alone in the park, and it was a good time and place to linger for a while reflecting on my three days in Palermo.

I came to Palermo on a whim that felt somewhat like a gamble. Leaving now, I realized that Palermo doesn’t ask for a plan; it only asks for your full presence and acceptance. Most importantly, Palermo isn’t a city you really “leave;” it’s one you carry with you until you inevitably return. And so will I. Soon.

You made Sicily move up to the top of my priority list!!!

LikeLike

Thank you, intrested reading.

LikeLike

What wonderful photos and adventures! God Bless You.

Respectfully Your Brother In Christ,

Fr. V.

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike