Luckily, there are still places in Europe where the nature feels untouched and the past history continues to deeply penetrate today’s living. The Outer Hebrides islands of Scotland are definitely one of such places.

The stern but stunningly beautiful landscapes of Hebrides are “resting” on the bedrocks which are among the oldest in Europe: they were formed in the Precambrian period, up to three billion years ago. People lived here since Mesolithic era (15,000 to 5,000 BC), and each “layer” of history is still visible through many archeological sites. The political ownership of Hebrides has changed over centuries: Vikings, Norway, Kingdom of Scotland, and now United Kingdom claimed their authority here. And yet, the islands’ everyday life remained under the control of the same powerful local family clans: MacLeods, MacDonalds, Mackenzies, MacNeils, etc.

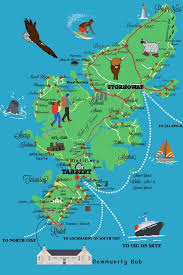

Geographically, Outer Hebrides is a chain of more than 70 islands (only 15 are inhabited) to the west of the mainland Scotland. Here is the map:

A trip to Hebrides has been on my bucket list for a long time, but I felt a need to find some good personal local connections there in order to properly explore and appreciate the islands. A perfect occasion emerged through the international hospitality network SERVAS.

I am a long-term member of SERVAS, and, it turned out, that the island of Lewis and Harris (the largest of Outer Hebrides) is home for two SERVAS members: Munro and Jane. A couple, they moved from the mainland to Hebrides 45 years ago, worked in the local administration (Munro) and education (Jane), retired and decided to stay for good. They invited me to come over and stay with them for a few days.

Out of 27,000 inhabitants of Outer Hebrides, about 21,000 live on the island of Lewis and Harris. It is a SINGLE island, but its northern part is commonly called the Isle of Lewis, while southern part is known as the Isle of Harris, as if they were separate islands. Why? The island is divided by mountains, and it was not until recently that a good road was built allowing for easy connection between two parts. Prior to that, the usual transportation between Lewis and Harris was by boat as if, indeed, traveling between two islands. And not only this. Lewis and Harris have clearly distinct landscapes (the former being comparatively flat and the latter having more than thirty peaks above 1,000 ft / 305 m.), and there are also many cultural differences between the two.

Both, Lewis and Harris, have seaports with ferries traveling to Scotland’s mainland. My hosts lived on the Lewis side, and I took a boat from the town of Ullapool on the mainland to Stornoway, the capital of Outer Hebrides which is located on Lewis. By the way, all connections with mainland and between the islands are provided by the same ferry company: Caledonian MacBrayne.

The journey is about 3 hours and costs only about 15 USD $ (more if you also transport a car). It was late afternoon when I left Ullapool.

Before entering open sea, the boat passed several islands. The ones closer to the coast had villages.

As we sailed further from the mainland, the passing islands looked wild and untouched by the humans.

It was getting cold on the observation deck and I went inside to explore the boat. Various announcements posted on the walls reminded me right away about where we were sailing. Indeed, most signs were in Gaelic – an ancient language which is related to Celtic culture and which was widely spoken in Scotland in 13-17 th. centuries. Today, only about 1% of Scotland’s population can speak Gaelic, but the Outer Hebrides remain “frozen in time” exception: more than half of people living there continue to use Gaelic language.

Overall, the ferry was very comfortable: it had spacious lounges, comfortable chairs, restaurants, special zones for children to play, etc.

My favorite place on the boat was the “Quiet Lounge:” a room with soft reclining chairs and – perfect for observation – big porthole windows.

Three hours of sailing went by quickly and Stornoway, the capital of Outer Hebrides, came into the view.

My host, Munro, met me at the port and we drove to his home in the tiny village of Keose, about 10 miles out of Stornoway. Munro’s house was impressive: a combination of traditional style with various added modern features. I was especially impressed by the inside “winter garden” and the dining room with floor-to-ceiling panoramic windows.

The village of Keiso looked more like a number of scattered farms: each surrounded by cultivated lands or pastures for various home animals. And, indeed, these were farms but of a very particular kind which is unique for Scottish Highlands and islands: these were the so-called “Crofts.”

In essence, crofting is a form of long-term land tenure and small scale food production by the families. Based on the 1886 legislation, it is a rather complicated system with landlords owning huge estates of thousands of hectares and individual crofters renting small parcels from them. Peculiar to this system is that while the land itself belongs to landlords, all improvements made to this land (i.e. houses, barns, plants, etc.) belong to crofters. A number of provisions allow crofters to keep the control over the land indefinitely and pass it within the family from generation to generation.

But then crofters also have some obligations and are expected to live on a croft and use the land productively. Further complication is that crofting is a system of combined individual and communal land-use. That is, individual crofts are established on the better land and belong to particular families, while the large areas of poorer-quality grounds are shared by all the crofters of a certain township/village for grazing of their livestock or other needs.

My hosts were also part of the crofting system, and upon arrival, I and Munro went to check out his sheep – the principal livestock of Hebrides.

Right next to the Munro’s sheep I discovered a cheerful pony which belonged to one of his neighbors.

I still did not met Jane, the wife of Munro. As it turned out, she was working on another property which collectively belonged to the village. What was she doing? She…was cutting the peat. Outer Hebrides have very little trees: moorlands dominate landscapes here. Consequently, dried peat has been traditionally used as a main fuel for heating the houses. Although increasingly replaced by modern sources of energy, peat remains an important asset for the people of Hebrides.

Cutting heavy soil into neat pieces and laying them in a particular manner for best drying is a truly “back breaking” job, and I was very impressed when I saw Jane doing this work.

Munro and I picked up Jane and we went back home. For my first dinner on Hebrides, my hosts served a traditional dish called “Duff.” It is a steamed pudding made of flour, suet, dried fruit and various spices. Being served warm and with generous portion of custard, it was delicious. If interested, HERE is a good Duff recipe.

Next day, Munro and Jane showed me some highlights of the Lewis part of the island. First destination were Calanais Stones, perhaps, the most iconic tourist attraction of Outer Hebrides. It is a giant structure of standing stones arranged in a shape of a cross and with a circle in the middle. Created in stages between 3000 and 2000 BC, Calanais Stones are of the same age and as impressive as famous British Stonehenge

It is unclear what the purpose of this construction was and how exactly it was built. Most popular theories suggest its usage as some sort of lunar calendar to help ancient inhabitants decide about timing for various agricultural tasks. Some see Calanais as symbolizing four winds or the signs of Zodiac. But then, the internal circle of the structure was also used as burial grounds: the ashes from cremated bodies were placed in clay pots and buried there. The whole place has been abandoned by humans at around 1000 BC and peat began to form over the site. Calanais Stones were uncovered again in 1857 after removal of 1.5 m / 5 feet of peat.

As if moving progressively from epoch to epoch, our next destination was the Dun Carloway Broch, the well-preserved ruins of the tower-like house. “Brochs” are Iron-Age tower-like multi-story houses. Their walls are constructed by the “dry stone” method: that is, without any mortar. Brochs are found throughout Atlantic Scotland, and some archeologists believe that they were used for military defense purposes. Others think that their primary purpose was to be the living quarters for the extended families of the most prominent local clans.

There are dozens of brochs’ sites on outer Hebrides dated from 100 BC to 100 AD. Among them, Dun Carloway is remarkably well preserved and it also features a dramatic setting overlooking Loch (sea inlet) Carloway.

To give you idea about its size, the external diameter of Dun Carloway is 14.3 meters / 45 feet and the walls vary in thickness from 2.9 to 3.8 meters (9 to 12 feet). It is unknown how heigh this broch was, but the remaining structure is 9.2 meters / 30 feet high.

It is unclear when and why the brochs were abandoned by their ancient inhabitants, but over centuries they were still occasionally used as fortifications and strongholds. One documented story is about an event in 1601. The family of Morrisons had stolen cattle from the family of MacAuleys, and they were hiding in the Dun Carloway. MacAuleys wanted their livestock back. One of them climbed the outer wall and smoked out Morrisons by throwing heather inside the broch and then setting fire to it.

As the centuries went by, the stones from the walls of the brochs were being reused to build new generation of dwellings which were very common in Outer Hebrides until recently: the so-called blackhouses. A traditional blackhouse had two concentric dry stone walls with a gap between them filled with earth. The roof was either thatched or made up of turfs. The windows were very small and most of them did not have proper chimneys. Hence when heated with burning peat, these homes were filled with a smoke. Livestock and other animals also lived in a separate section of a blackhouse

It is believed that the name – “blackhouse” – derived from the comparison to the new – “white” – homes which were built since the late 1800’s.

While being increasingly replaced by the modern homes with indoor plumbing, electricity, and other conveniences some blackhouses were inhabited until the middle 1970’s (although with added fireplaces and chimneys, instead of the chimney free traditional construction).

The very last families still living in the traditional blackhouses were those in the Gearrannan Village. After they also left in 1974, it was decided to preserve the village and to use part of it as a museum and part as holiday accommodations for tourists. And so, the Gearrannan Blackhouse Village was our last destination for the first day of exploring of Lewis & Harris island.

Gearrannan Village offers much more than simply wandering and looking around. Here, you can truly travel back to mid 1950s and experience the life in a blackhouse by yourself. Indeed the interiors of several homes are carefully restored and replicate actual life conditions back then. Several volunteer docents wait for you inside and will explain how different tools and various rooms of the homes were being used in the past.

So, step inside, enjoy the warmth and fragrance of a peat fire, look at the demonstration of weaving of the famous Harris Tweed, and “meet” the original inhabitants of the houses through the multi-media presentations depicting their lives and challenges.

People who want to fully immerse themselves in the life in a blackhouse can actually stay overnight here. One of the homes has been converted into a youth hostel, and four became self-catering accommodations. Their exteriors and interiors retained traditional appearances, while offering all the conveniences of a modern home: full kitchen, central heating, electric showers, snug beds. Check out reservations and prices HERE.

And here is one more recommendation about visit to Gearrannan. When you are done with museum, stroll through the village towards the ocean and walk a narrow stone path which descends to the shore.

Then you will have two options for a perfect coastal walk. One will take you to the north, over the rugged terrain and to the beach at Dalmore village. The trail is well marked and you need 2-3 hours for this hike. A second, much easier option, is simply to stay on a stone path from the village. Just, in a few hundreds yards, you will reach a small pebble beach – a good place to relax and enjoy fresh salty breeze.

Next day, I decided to go for a hike. The island’s scenery is so appealing that there is no need to search for a particular route. Any destination will reward with great views and colors. The landscapes of the northern (Lewis) part of the island are shaped by endless moorlands many “lochs” – a Scottish Gaelic word for a lake or fjord. When the skies change their colors (because of the “come-and-go” clouds), so do the surfaces the of the lochs transitioning quickly from the deep blue to nearly black.

My destination for a hike was an old cemetery. By the way, the funeral business on Outer Hebrides is also greatly affected by natural conditions. In most places, under thin layer of soil you will encounter a solid rock. As a result, there are very few plots which could be used as cemeteries and with a possibility to dig a proper grave. When such plot is filled up to capacity, the islanders need to find another chunk of land with deep enough soil. Hence, in many instances a cemetery could be far away from a village where a deceased lived.

Some peculiar social consequences stem from these circumstances. One is a tradition that only men accompany coffin for the last journey. That is because the walking distances to cemeteries were too long and too harsh for the women, and they also needed to stay home in order to prepare a proper meal for men, when they would return – fairly exhausted – after walking and hauling coffin to a cemetery.

The other issue is finding a space for another coffin in the same grave when several family members are buried together. In many instances this requires “shuffling” coffins between the rocks beneath the surface. As a result, after many years, no one can tell for sure whether a name on headstone (or a cross) actually corresponds with remains laying underground.

The “old cemetery” is called so, because it reached full capacity and has no spots for new graves. It sprawls over the slopes of a hill and offers good views of surroundings. I walked between the graves reading names, dates and last words devoted to deceased.

In the afternoon, Munro took me to the museum in Stornoway. The museum is new, but it is adjacent to the Victorian era Lews Castle. The Castle was built in 1840s as a residence for Sir James Matheson who had bought the whole island (yes!) a few years previously with his fortune from the Chinese opium trade. Later, the Castle changed hands several times, eventually becoming a dormitory for college students and, simultaneously, going into disrepair and decay. Luckily, about ten years ago funds were found to restore the castle to its original glory. Today, it houses a cultural center, nice cafe and luxury holiday accommodations. It is open to the public and I highly recommend to check it out.

As to the museum, I liked a lot that it was not overwhelming in size. Rather it is like a “boutique” exhibition with just several rooms showing the snapshots and key-moments of history and present day life on Outer Hebrides. The exhibits also combine nicely audio and video information, and one room screens the movie about the islands which is projected on all four walls.

For me, the highlight of visit were the “Lewis Chessmen” – the 12th century chess pieces made out of Walrus ivory which were found in 1831 at Uig Bay. Not only are these one of the few surviving relatively complete medieval chess sets, but they also belong to the epoch when the islands were under Norwegian Kingdom – a period which left little historical evidences and artifacts. A number of unanswered questions surround Lewis Chessmen and all these hypothesis are discussed in the exhibit. Historical importance aside, I simply loved the elegant appearance of all figures: kings, queens, bishops, knights, warders and pawns.

On the last day, Munro took me on an expedition to the southern part of the island – the Isle of Harris. In the recent past, “expedition” would actually be a good word for a journey between Lewis and Harris parts of the island, because the natural boundary between them is formed by range of mountains crossing from from Loch Seaforth in the east to Loch Resort in the west.

It was not until 1920s that a good road was built allowing for easy transportation between Lewis and Harris. Prior to that, people would either “backpack” through the mountains or – more typically – travel by boat as if sailing between two real islands. Here is the map showing a divide between Lewis (red) and Harris (blue) parts of the island.

Today, A859 road travels 93 km / 58 miles from Stornoway on Lewis to the village of Rodel at the southern tip of Harris. Yet, while on the mostly flat Lewis side A859 is always a nice wide two lane highway, some of its portions on a more mountainous Harris side are still single rough tracks: so, the oncoming cars need to “negotiate” who goes forward and who backs.

But even after A859 construction, some townships remained isolated and inaccessible by car. A village of Rhenigidale on the eastern coast of North Harris did not have a road until 1990s. The “life line” connecting it with civilization was “Postman’s Path,” a 10 km / 7 mi trail through the mountains to the town of Tarbert (the “capital” of Harris). The postman would walk this path three times a week delivering not only mail, but also vital supplies like medicines, etc. Today, if you fancy a strenuous but spectacular hike, walking “Postman’s Path” is one of the best options on Lewis & Harris.

“Postnman’s Path” is also regarded as of the best European mountain biking trails.

Myself and Munro, however, crossed from Lewis into Harris in a modern and more comfortable way, by car.

Our first stop was in the village of Tarbet, the “capital” of Harris. With population of about 1,200 it is about four times smaller than Stornoway. Yet, there is a number of reasons to spend here at least a few hours. First, it has a fairly attractive natural harbor with ferries running from there to the Uig on Scotland’s mainland.

Second, being spread over several hills surrounding harbor, the whole town looks neat and appealing.

Third, Tarbert has two excellent options for shopping and taking home some souvenirs or presents from Outer Hebrides. One is locally produced tweed, a traditional Scottish rough woolen fabric with yet soft texture. In Tarbert, right next to the harbor, there is a great store selling huge variety of tweed clothes.

Made in variety of colors, blazers, hats, coats, scarves – all is available in this little store.

Another option for shopping is locally made whisky and gin. The Island of Harris Distillery is also right next to the harbor and – besides having a store – it offers guided tours with tasting of all its products.

Being a wine drinker, I am not an expert on strong drinks, but apparently the usage of sugar kelp seaweed from the seas around the islands makes Harris gin unique in flavor.

As to the whisky, a single malt Hearach will cost you about 60 pounds / 76 USD, but considering its maturation (minimum of 10 years in barrels) and fancy crystal bottle, it might be not a bad option to spend money on something which would remind on your trip to Lewis & Harris.

After couple of hours in Tarbert, we drove further south through the Harris inlands. I was amazed how different scenery was compared to what I have seen on Lewis side. Instead of wide green pastures, I saw much more rocky hills, stones and lochs with bizarrely changing colors of water.

Sometimes, in the distance, tiny coastal villages would appear being laid out along fjord-like sea inlets.

The southern tip of the Isle of Harris is in the village of Rodel. The main attraction here is 15th century St. Clement’s church which is the only surviving medieval church on Outer Hebrides. With the tower built on a rocky outcrop at the end of the nave and sparse but elaborated interior it is a fascinating place to end a journey across the Isle of Harris.

For the true lowers of church architecture, one more thing should be mentioned about St. Clement’s. In 1528, Alasdair Crotach MacLeod, the chief of the most powerful family clan in Harris, prepared for himself a magnificent wall tomb on the south side of the choir. Being crowned by an arch and ornated by carvings, it is considered one of the finest medieval wall tombs in Scotland.

The Isle of Harris ends in Rodel, but our trip was far from completion. Instead of taking the same road back home, Munro drove to the west coast of Harris, and then along the coast heading north, towards Lewis. This drive brought another surprise with the scenery. I did not expect that the Outer Hebrides may have such gorgeous white sand beaches.

Our first stop was at the “Isle of Harris Golf Club” which overlooks Sgarasta Mhor Beach. No one was playing there when we arrived, and I simply walked the grounds absorbing wide open views, enjoying sunshine and salty air. If you are a golf player, I guess, playing here would be one of the most memorable experiences of your life.

The picture above is facing towards south. Turning my head in opposite direction, I had a feeling that the wind created smooth waves not only in the ocean, but also in the green meadows which surrounded me. I swear, I even heard the sounds of these “grassy waves.”

As we drove further north and along the coast, it was clear that this part of Harris attracts some people with substantial means. Indeed, I saw quite a few upscale houses with interesting architecture.

Also here, one local businessman reconstructed a full-scale “broch:” remember, I wrote about these Iron-age tower-like drystone homes at the beginning of this story. Called “The Broch at Borve Lodge Estate,” it offers accommodations to anyone who is willing to pay about 2,500-3,000 pounds (3,200-3,800 USD) for one week of “ancient style” living. The website of this lodge says that “this is the first broch built in Scotland since the Roman era” which offers “5-star 21st century comfort in an Iron Age Tower.” Regrettably, I did not have sufficient funds to check out the second part of this statement. So, if any of my readers decide to stay there, please let me know how did it go.

Nevertheless, despite these occasional appearances of wealth and modernity, the west coast of Harris still feels fairly untouched by humans. Sea, wide sand beaches, pastures and meadows, rocks and herds of sheep – this is what you will mostly observe while driving A859 up north.

We passed a few more beaches without stopping, because Munro was eager to show me his favorite one: the Seilebost beach near the village of the same name. To get there, you need to park car near the old Seilebost school house and then go for a short hike. In exchange for this little effort, you will be presented with a wide strip of a fine white sand which offers a stark color contrast with the bright green ocean. The high sand dunes surrounding Seilebost beach are additional bonus allowing for a great view in all directions.

After relaxing at Seilebost, we drove back to Munro’s home in Keiso village. It was fairly late when we arrived, but in early June there is almost no real “night time” on Lewis & Harris. It still felt as early evening, when we sat with Munro and Jane for an abundant dinner in their sunlit and glass-covered dining room. I felt immensely grateful (or, perhaps, “blessed” is better word) for the three days of full immersion in the culture, nature, and every-day life of Lewis & Harris.

The next morning, at 7.00, I boarded again the Caledonian MacBrayne Ferry, walked to the open upper deck of a boat and said “Good bye!” to the island which was slowly disappearing in the distance.

Then I settled in the “Quiet Lounge” with a cup of hot coffee and opened a package of oatmeal cakes produced in Stornoway. Although I was leaving the place which I liked a lot, I was not sad at all. Why? Because I knew for sure that I will be back soon on Lewis & Harris: to meet more people, to walk Postman’s Path, to have a full day on Seilebost beach, to help Jane and Munro in their “crofting” work and…who knows what else will wait for me there.

Not interested in your websited. ________________________________

LikeLike

very special and interesting trip! thanks for writing! Jacqueline

LikeLike

Thanks nice place!

LikeLike