When I talked with friends about plans to visit Bosnia & Herzegovina, most of them would ask: “To visit what?” The other common reaction was: “Really? Why bother?”

Situated on the Balkan Peninsula, Bosnia & Herzegovina (informally known as “Bosnia”) is a country in southeastern Europe. With a population of about 3,5 million and a territory of 19,800 sq mi / 51,200 sq km, it is a small nation. And, yet, it offers an amazing array of natural, cultural and historic attractions. Here is Europe’s map: take a look where Bosnia is.

Even people who heard about Bosnia do not realize how appealing this country is for any kind of travel. Visually, it captivates with the dramatic peaks of the Dinaric Alps, emerald-green rivers and lakes carving through lush valleys, cascading waterfalls, and pristine ancient forests.

This natural splendor is interwoven with a mosaic cultural tapestry, where centuries of Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian influences are etched into ancient fortresses and bridges, picture-perfect towns, vibrant markets, and the diverse traditions of Bosnia’s peoples.

Also, if you are one of those who travels for culinary adventures, Bosnia won’t disappoint you either: the people of Bosnia love to eat, and their cuisine is rich with many unique dishes.

Last but not least, by European or US standards, Bosnia is a fairly comfortable country to travel, but it is VERY inexpensive. You will find nice accommodations for US$ 25-40 per night and get a good meal for US$ 10.

I spent 12 days in Bosnia in May 2025 and barely scratched the surface of this country’s many highlights. This story will tell what you can see, do and experience in this – indeed – hugely underrated country.

However, in order to have a truly rewarding journey in Bosnia, you also need: a) to know a few travel practicalities, and b) to be aware of some sensitive moments in Bosnia’s complex history and culture. If you decide to visit this country, I highly recommend reading the first two sections from the below table of contents. Otherwise, you can skip HERE straight to the story about the trip.

- Five Practicalities About Traveling in Bosnia & Herzegovina

- Important Things to Know About Bosnia’s Past and Present

- Sarajevo: a Colorful Snapshot of the Nation

- Two “Must Visit” Tourist Spots: Mostar and Blagaj

- Best Wines and Most Beautiful Walled Town of Bosnia

- My Favorite Town: Trebinje

- Mountains, Glacial Lakes and Wild Horses: Sutejska National Park

- Once the Capital of Bosnia: Travnik

- It Is All About Water: Jajce

- Just a Nice “Normal” Town: Tesanj

Five Practicalities About Traveling in Bosnia & Herzegovina

- The best time to visit Bosnia is April-May and September-October. The weather is pleasant and warm, with landscapes blooming with wildflowers and lush greenery (spring) or offering stunning foliage (fall). These months are ideal for both outdoor activities (like exploring the national parks) and sightseeing in the cities (with fewer crowds than in peak summer).

2. Money. Bosnia’s currency is called “Convertible Mark (BAM),” but locally, on price tags, it is often abbreviated as KM. The exchange rate of the BAM to the Euro is fixed at 2 BAM for 1 Euro. But Euros are also commonly accepted in Bosnia when paying in restaurants, hotels, or markets.

3. Transportation. You can travel in Bosnia by public transportation via train and, most importantly, intercity buses. They are cheap and reliable. However, if you want to discover the “harder to reach” corners of the country (national parks, small towns and villages), I strongly recommend renting a car. The roads are good, and car rental prices are affordable. I rented an Opel Crossland, a subcompact crossover SUV. For a nine-day rental with full insurance coverage, I paid about US$ 500.

4. National Parks. For a small country, Bosnia has a remarkable variety of natural landscapes, and it is home to four national parks: each offering a unique natural setting and biodiversity. Try to include these parks in your travel plans.

The most important is Sutjeska National Park which actually spreads across borders, being partially in Bosnia and partially in Montenegro. It is renowned for the Perucica primeval forest, glacial lakes, and the country’s highest mountain, the Maglic peak.

5. Food. Bosnians love to eat and you will find an abundance of affordable cafes and restaurants pretty much everywhere: even along highways, or on the shores of lakes and rivers. Here are a few “iconic” Bosnian food items you should try.

One is Bosnian coffee. It is served on a metal tray with three components: a strong coffee in “dzezva” (small pot with a long handle , typically made of copper or brass), a sugar bowl, and a glass of cold water. The coffee from “dzezva” is then poured into small cups and drunk intermittently with sips of cold water.

“Cevapcici” (also known as “cevapi”) are considered a national dish of Bosnia. These are small flavorful sausages made of minced beef. They are served inside warm flat bread “somun” and accompanied by chopped onions and sour cream or yogurt.

When it comes to dairy products, Bosnia makes a variety of good cow, goat, and sheep-milk cheeses. But a more unique item is “Kajmak.” It is a rich and creamy spread prized for its luscious texture and distinct, slightly tangy flavor. It is served with fresh warm bread or as a side dish.

Depending on the duration of maturation, there are two types of Kajmak: young/”mladi” (softer texture, sweeter taste) and mature/”stari” (firmer texture, yellowish color, and a more complex flavor).

Finally, when traveling in Bosnia, you will find a lot of bakeries (“pekaras”). Besides various breads and pastries, they offer another typical dish: “pita.” Essentially, “pita” is a pie made from a thin elastic dough which is filled with a variety of ingredients and then coiled into a spiral or arranged in rows in a baking pan.

Depending on the filling, there are four types of pita: “burek” (minced meat), “sirnica” (fresh cheese mixed with sour cream), “zeljanica” (spinach and cheese), and “krompirusa” (diced potatoes with onions). A key to making good pita is an ancient baking method called “iz pod saca” (from under the sac). This method involves using a “tepsija” (shallow metal or ceramic pan) and a “sac” (a heavy, dome-shaped lid) which is covered with hot coals.

When properly prepared and served hot, pita is a delicious and very affordable meal. A hearty portion typically costs only about US$ 2.

In the next section, I will give you a crush-course on Bosnia’s complicated history and politics. This information is truly important if you want to fully understand the realities of life in present-day Bosnia. But, again, feel free to skip HERE to the story about my journey.

Important Things to Know About Bosnia’s Past and Present

Bosnia & Herzegovina is a young country, but it has a long and complex history. Indeed, the past and present of this nation were shaped by many influences and events, and each left its indelible imprint on how this country looks now.

In its current political form (federal parliamentary republic) and within its present borders, Bosnia & Herzegovina has existed only since 1995.

However, in the distant past, Bosnia already had experience with independent statehood. In the 12th century, the Banate of Bosnia was established, and by the 14th century it had evolved into the Kingdom of Bosnia. At its zenith, the borders of this medieval state extended into areas that are now parts of present-day Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia. The town of Jajce was the capital of Bosnian Kingdom.

One curious fact about religion reflects the independent spirit of the Bosnian people. In the times of the Bosnian Kingdom, different parts of southeast Europe were dominated by Roman Catholic or Orthodox Christian Churches. In Bosnia, however, most people belonged to the “Crkva Bosanska” (i.e. “Bosnian Church”), an independent Christian Church which developed its own practices and style of worship.

Crkva Bosanska drew from both Western (Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) religious traditions but maintained its full independence. Subsequently, it was accused of heresy by both Rome (Roman Catholicism) and Constantinople (Orthodox Christianity).

In the mid-15th century, Bosnia was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. The new rulers brought new religion, Islam, and moved Bosnia’s capital to the city of Travnik.

In the late 19th century and through World War I, Bosnia was annexed by the Austro-Hungarian empire. This short period was a truly transformative era. It brought modernization in terms of infrastructure (rail lines, new roads and industries), social arrangements (land reform, changes in the legal system, the introduction of parliament), and education (Western-style schools and universities).

Culturally, Austro-Hungary firmly drew Bosnia into the European orbit. Bosnian Muslims, who were part of the ruling elite under the Ottoman Empire, became a minority within a European Christian state. The use of the German language was encouraged in education and official settings.

Austro-Hungarian Empire crumbled in the wake of WWI. The new state, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, was formed on the Balkans, and Bosnia became part of it. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia was ruled by the Serbian dynasty of Karadordevic, and it brought under one roof many ethnic (Bosniaks, Serbs, Croats, Slovenes) and religious (Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Muslims) groups.

Politically, however, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a shaky formation. During WWII, when Germany invaded the country, the young King Peter II (he was only 18 at the time) and his government escaped to the United Kingdom. In their place, different alliances and forces emerged. Some fought against the Germans for a new democratic Yugoslavia that would grant equal rights for all constituent groups; some also resisted the Nazis, but wanted to restore the pre-war monarchy which would be essentially controlled by the Serbs; and still others embraced fascist ideology and supported the Nazi invaders in the hope of creating a state “purified” of Serbs, Jews, and Roma people.

The group fighting for a democratic Yugoslavia, the “National Liberation Army,” was led by a charismatic commander, Josip Broz Tito . After Yugoslavia’s liberation in 1945, Tito became the country’s leader until his death in 1980: first, as prime minister and then as president.

The country was transformed into the “Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia” with Bosnia & Herzegovina being one of six constituent republics (the others were Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, Slovenia, and Macedonia). For several decades, Yugoslavia was a “showcase” nation that successfully blended market approaches in its economy with Socialist ideology, and where all ethnic and religious groups seemed to live happily together.

But things started to deteriorate after Tito’s death (1980), and in 1991, Yugoslavia broke apart. Essentially, at that time one-by-one, the constituent republics declared their independence from the Federal Center in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. The Civil War followed with different forces pursuing various goals.

Of all parts of ex-Yugoslavia, Bosnia & Herzegovina was the most affected by the cruelty and fighting. The Bosnian war lasted three years (1992-95), and it took the lives of about 100,000 people, a staggering number for a nation of only 3,5 million. The main dividing line was between two demographic groups: Muslim Bosniaks (who wanted full independence for Bosnia) and Orthodox Christian Serbs (who wanted to keep ties with Serbia).

The war ended in late 1995 with assistance (and pressure) from the United States and Western European nations. The signing of the Dayton Agreement opened the present chapter in Bosnia’s history and laid out the fundamentals of the newly born state.

Demographically, the population of Bosnia & Herzegovina consists of three main groups: Bosniaks (50%), Serbs (31%) and Croats (16%). While formally these three groups are recognized as separate ethnicities, the reality is somewhat different. Essentially, all three speak the same language and have a similar culture with primary distinction being religion: Bosniaks are Muslims, Serbs are Orthodox Christians, and Croats are Catholics. While traveling in Bosnia, you will often see side-by-side all different places of worship: Mosques, Orthodox and Catholic Churches.

Despite their cultural and linguistic similarities and the peaceful day-to-day coexistence of all three groups, these religion-based divisions continue to play a huge role in the politics of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Being technically a liberal democracy and parliamentary republic, the political and administrative structure of Bosnia & Herzegovina is much more complex than one would think.

First, as a result of the 1995 Dayton Agreements, peace implementation and civil life in the country are supervised by the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina. Remarkably, the High Representative is a foreign national (a citizen of one of the European countries) who has the highest political authority in the country. In fact, due to the vast powers of the High Representative, this position has been often compared to that of a viceroy.

Second, although the country is officially known as “Bosnia and Herzegovina,” in reality it is a union of two entities: the Federation of Bosnia & Herzegovina and Republika Srpska. The latter occupies nearly half (49%) of the country, has a predominantly Serbian population (82%), and exercises vast autonomy (nearly independence) from the national government in Sarajevo. When traveling in Republika Srpska, you will never see the national blue and yellow flag, but only the red-blue-white tricolor flag of Republika Srpska.

Finally, the head of state of Bosnia and Herzegovina is NOT a single person, but a three-members body called the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The three members are elected for a collective four-year term and each represents one of the main demographic groups: Bosniaks, Serbs, and Croats. To make things even more complex, one of the three serves as the Chair of the Presidency, but this chairmanship rotates among them every eight months.

After reading this section, I suspect that you may think that the current peace and democracy in Bosnia & Herzegovina are fairly fragile. Indeed, they are. But the good news is that while traveling in all parts of the country, I never witnessed a hostile attitude from a member of one group towards another.

The older generation remembers well the brutalities and hardships of the 1992-95 war and wants no repetition. For young people, on the other hand, the conflicts, fights and bad memories of the past are simply irrelevant. All they want is to have a good life similar to their peers in neighboring EU nations (Bosnia & Herzegovina is a candidate for joining the European Union).

Most importantly, as a visitor, I was given warm welcome in all parts of the country and by all people I met along during the trip.

Sarajevo: a Colorful Snapshot of the Nation

Sarajevo (population 275,000) became the administrative center of Bosnia & Herzegovina in the mid 19th century, during the later stages of Ottoman rule. After the Austro-Hungarian Empire annexed Bosnia & Herzegovina (1878), the city retained its central status. And so, today, Bosnia’s national capital greets visitors with a tapestry of Oriental and European influences and traditions.

I have landed in Sarajevo at around noon, took a taxi to the city (25 Euro, 15 minutes), and settled in an apartment I found on Booking.com. Called “Apartment in Old Town,” it was right in the city’s historic center and attracted me by many praising reviews from previous guests. A big draw was also its outdoor terrace with panoramic view of Sarajevo.

Indeed, the view from the terrace was so impressive that instead of heading straight into the town, I lingered there simply sipping coffee and absorbing the surroundings.

On Google maps, I found a place called “Viewpoint of Sarajevo.” It was only a 20 minutes walk from the apartment, and I went there to take a look at the entire city. Stretched along the Miljacka river, the whole city was literally in the palm of my hand.

Afterwards, I walked down to the most iconic landmark in Sarajevo, the Sebilj, an ornate wooden fountain that stands in the middle of Baščaršija Square. The fountain was initially built in 1753, during the Ottoman era as a kiosk-like public source of water. Back then, Sarajevo boasted hundreds of such fountains, quenching the thirst of its citizens and visitors alike. Regrettably, the original Sebilj, along with many others, was destroyed in a devastating fire, in 1852.

Forty years later, during the Austro-Hungarian period, the Sebilj was reconstructed by the Czech architect, Alexander Wittek. While Wittek was respectful of the fountain’s Ottoman heritage, he designed it in a pseudo-Moorish style, a popular architectural trend of the time. Hence the “new Sebilj” is not a replica but a cultural reinterpretation, embodying the new influences shaping Sarajevo at the turn of the 20th century.

The many pigeons flying around Sebilj made me think of St. Mark Square in Venice.

The area around Sebilj is called Bascarsija. It is Sarajevo’s historic Old Town and main tourist destination. Narrow cobblestone streets, Ottoman-era houses, small shops selling handmade copper goods, carpets, and local food delicacies – this is Bascarsija.

Bascarsija is also a good place to try traditional Bosnian coffee which is both a drink and a ritual. If you skipped the introductory section, read about Bosnian coffee HERE.

Predictably, Bascarsija has many restaurants offering traditional Bosnian dishes. Again, if you skipped the introductory section, read about various Bosnian foods HERE.

Although the Old Town’s restaurants were tempting, I had another plan for the first dinner in Sarajevo. Instead, I walked to Markale, a historic covered market which sells all kinds of Bosnian traditional food products.

Bosnia is known for various sausages and smoked meats. So, if you are a meat-lover, definitely check them out at Markale.

I was, however, looking for some interesting cheeses. And yes, in Markale, you can find cheeses produced in all parts of the country.

After loading up on cheeses, I walked to a tiny eatery called “Tepsija” which is right next to Markale. It is a real hidden gem totally overlooked by tourists. The only thing Tepsija makes and serves (either for dine-in or take-out) are traditional Bosnian “pitas,” the pies with various savory fillings: minced beef, fresh cheese, spinach, or potatoes.

I wrote about the “art and science” of making genuine pita in the introductory section HERE, and Tepsija has definitely mastered this art to perfection.

After getting all supplies at Markale and Tepsija, I returned to the “Apartment in Old Town.” Dinner was served “al fresco,” on the terrace, with a great view over Sarajevo at night.

The next day started with a walk along the Miljacka river which bisects Sarajevo. This leisurely stroll is a great way to explore the mosaic cultural heritage of the city. Indeed, the fine architecture on both sides of the river represents various styles and eras, tracing the many layers of Sarajevo’s history.

One of the highlights on this walk is the City Hall known locally as “Vijecnica.” Built in 1894, it originates from the times of Austro-Hungarian rule. And yet its strikingly bright Moorish ornamentation reminds us that Sarajevo has always been at the intersection of two cultural influences: European and Oriental, Christian and Islamic.

Speaking of religion, Sarajevo has always been known for its religious diversity. At certain point, it was even nicknamed “European Jerusalem.” Today, Muslim Bosniaks constitute the majority of inhabitants, but both Orthodox Christian Serbs and Catholic Croats also form sizeable portions of the city’s population. And so, Sarajevo has many worship places representing these religious traditions. Muslim mosques, Orthodox Christian and Roman Catholic Churches stand often right next to each other.

I will share with you my three favorite religious sites: one – for each group. For Muslim experience, most guidebooks suggest visiting the Bascarsija Mosque. It is in the middle of the Old Town and has a status of a National Monument. For my taste, however, the Ali Pasha Mosque offers a more authentic and intimate atmosphere.

Also, the Ali Pasha Mosque is like an informal neighborhood center. At any time, you will see there people not only praying, but simply sitting together and discussing quietly whatever needs to be discussed. A cozy courtyard, a garden and a cemetery surround the Mosque. Many gravestones are dated 1992-95 testifying to all the unnecessary deaths during the Bosnian war (I wrote about it HERE).

The main worship place for Sarajevo’s Orthodox Christians is the mid-19th century Cathedral of the Nativity of the Theotokos.

Yet, another Orthodox Church in the city has much deeper historic roots and offers an atmosphere of quietness and respite. This is the Church of the Archangels Michael and Gabriel which is also known simply as the “Old Orthodox Church.” Historians argue about the original date of its foundation (with some suggesting even the 5th-6th centuries), but the present building has existed since 1730.

A solid stone wall separates the Old Orthodox Church from the street, and many people pass by not even noticing it. But the gates are usually open: so, go through, walk around the carefully manicured courtyard, and then explore inside.

The main treasure of the Old Orthodox Church is its carved iconostasis with icons dating back to the 1670s. Except during worship services, the chances are great that you will have the whole place to yourself. And here is one more tip. In the corner, there are stairs leading to the second floor and gallery. From there, you will get the best view of the entire interior with all its icons, ornaments and decorations.

The main Roman Catholic Church of Sarajevo, the Gothic-style Sacred Heart Cathedral, sits on a very busy square, all sides of which are occupied by shops, restaurants, and open-air cafes.

However, when you go inside the Cathedral and close its massive doors behind you, all the street noises and disturbances disappear instantly. Instead, quiet organ music, majestic marble altar, religious murals, and colorful stained glass will immerse you in an entirely different reality.

If any place in Sarajevo can claim to have made a worldwide impact, it is the Latin Bridge. Here, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated. This event is widely considered to be the catalyst for outbreak of the World War I which lasted over four years and took the lives of about 20 million people.

Right next to the Latin Bridge, there is a small (just one large room) museum which I highly recommend. It combines the history of the assassination with a broader picture of how people lived in Sarajevo when Bosnia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1878-1918).

At the museum, I learned a curious fact regarding the Archduke’s assassination. It was a Serbian student, Gavrilo Princip, who fired the fatal shots, but the plot also involved several people placed along the Archduke’s motorcade route. Before Princip succeeded, another conspirator, Nedeljko Cabrinovic, had thrown a bomb at the Archduke’s car. It exploded and injured several bystanders, but not the intended target.

Well, instead of ceasing his procession through Sarajevo and evacuating, the Archduke continued along the planned route, coming eventually to the spot where Gavrilo Princip was waiting. I guess that back then, secret service protocols were not as efficient as they are today.

Another “a must visit” exhibition is the Sarajevo Siege Museum. In the introductory section (HERE), I wrote about the civil war in Bosnia which erupted after the break up of Yugoslavia and lasted three years (1992-95).

During this war, Sarajevo was controlled by Muslim Bosniaks fighting for Bosnia’s independence, but the city was completely surrounded by Serbian troops. The siege of Sarajevo lasted 1,425 days making it the longest siege of a capital in modern history. The Siege Museum is about the realities of living in a city which – for nearly four years – was under constant shelling and disconnected from the rest of the world.

My very full day of exploring Sarajevo was properly “crowned” with a dinner in the “Inat Kuca” restaurant which is also known as the “House of Spite.” It serves traditional Bosnian dishes (read about Bosnian foods HERE) and has appealing folkloric interiors.

There is an interesting story related to Inat Kuca. Originally, this building stood on the other side of the river and was owned by an elderly man named Benderija. It was a prime spot chosen by the Austro-Hungarian administration (this was in the 19th century) as the place to build the new City Hall. Benderija, however, staunchly refused to allow his home to be demolished, despite numerous offers and pressure from the foreign rulers. For Benderija, it was more than just a house: it was his “rahatluk,” his place of peace and comfort.

Finally, Benderija agreed to vacate the spot, but under two conditions. First, he demanded a bag of gold coins. Second, he asked for his house to be moved – brick by brick, stone by stone – to the opposite bank of the Miljacka River, directly facing the place where the new City Hall would stand. Left with little choice, the Austro-Hungarians conceded to both demands.

The house was then aptly named “Inat Kuća”, and it became a symbol of local defiance against a powerful empire and a lasting monument to Bosnian stubbornness, the “inat.”

After dinner, I walked back to the “Apartment in Old Town,” poured a glass of wine, and sat on the terrace. Looking at the city’s skyline, I said “Good night” to Sarajevo, a small capital which offers so much for a curious visitor.

A big THANKS goes to Riad, my host and the owner of the “Apartment in Old Town.” Staying there definitely added to the feeling of “full immersion” in Sarajevo’s life and culture. If you decide to visit Sarajevo, you can reserve “Apartment in Old Town” on Booking.com or get in touch with Riad via WhatsApp: +387-644-027-394

Two “Must Visit” Tourist Spots: Mostar and Blagaj

Each country has places where – for various reasons – most tourists go. I usually try to avoid these overcrowded spots, but I decided to make an exception for the UNESCO World Heritage Site town of Mostar and the iconic Dervish Monastery in Blagaj. These were my first destinations in the 9-days trip through Bosnia & Herzegovina. As I wrote in the introductory section, having a rental car is the best option to explore this country.

The drive from Sarajevo to Mostar (about 2 hours), is a visual delight. After the town of Konjic, the highway E73 meanders along the shores of Jablanica Lake and then the Neretva River. This is a very scenic route: take your time and enjoy.

Along the highway, you will encounter many restaurants: each offering fresh fish and the scenic (right by the water) setting. I stopped for lunch at restaurant Kovacevic.

Another 40 minutes and I arrived in Mostar, a town in southeastern Bosnia which was awarded the status of UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. The main draw here is Stari Most (“Old Bridge”), a 16th-century Ottoman era masterpiece.

Beyond the bridge, visitors usually explore the picture-perfect Old Town with its blend of Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian architecture, shop for traditional products and handicrafts (cashmere scarfs, copperware, woodcarvings, rugs and kilims), and simply enjoy the atmosphere of the permanent open-air “party.”

Here is one recommendation: before going to the main tourist area, make a stop at the Karadoz Beg Mosque, pay 5 Euro entrance fee, look at its elegant interior decorations, and – most importantly – climb the narrow stairs to the top of the minaret. From there, you will get an excellent 360 degree view over Mostar.

Why is Mostar’s Old Bridge such a big deal? First, it is an architectural and engineering marvel. Completed in 1566, it became an exemplary piece of Islamic Balkan architecture. The bridge was constructed as a single hump-backed arch with a span of 30 meters (98 feet), and it was built without any foundations. Instead, the 24 meters (79 feet) tall structure uses abutments of local limestone anchored directly into the waterside cliffs.

Second, the bridge became a symbol of Bosnia’s both unity and division. The original structure stood for 427 years, surviving numerous conflicts and symbolizing the coexistence of diverse ethnic, and religious communities (Muslims, Croats, and Serbs).

Tragically, Stari Most was destroyed in 1993, during the Bosnian War. The decision to rebuild the bridge (2004) exactly as it was, using original techniques and salvaged stones, was seen as an expression of reconciliation and hope for a peaceful future.

Finally, the Old Bridge is famous for its daring divers, the men of Mostar who leap from the bridge into the cold Neretva River. This risky feat requires skill and training, and it is seen as a rite of passage that dates back centuries. The chances are great that while visiting Mostar you will witness this “free diving show.”

The most picturesque part of Mostar’s Old Town is on the right side of the Neretva river. Simply walk randomly through the narrow cobblestone streets: each “turn and corner” will offer great views.

One place many tourists miss (because they are not aware of it) is the Crooked Bridge. It was built (1558) before the Old Bridge being used as a test run for the larger “Stari Most.” Remarkably, unlike the Old Bridge, the Crooked Bridge survived the Bosnian war, but – alas – was destroyed by floods in 2000. Yet, it was quickly reconstructed and reopened in 2001.

Unless you are interested in shopping for souvenirs and handicrafts, or decide to eat in one of the many restaurants, 2-3 hours are enough to explore the historic sites of Mostar. The next popular destination is just 20 minutes away by car: the village of Blagaj.

Its main attraction is a 16th-century Dervish monastery, another showcase of Ottoman and Mediterranean architecture. Dervishes are members of Islamic Sufi mystical orders, who are known for their spiritual practices (chanting, whirling dances) aimed at achieving direct communication with God and a state of ecstatic trance.

Blagaj Tekija (name of the monastery) is nestled at the base of a 200 meters / 600 feet cliff with Buna River emerging from a karst spring located in a cave directly beneath the cliff.

Built around 1520, the Monastery includes a guest house, a mausoleum containing the remains of some Islamic Saints, and rooms for prayer and Zikr chanting. For Muslims, Blagaj Tekija remains an important pilgrimage site, while tourists are also permitted to visit and explore the entire complex. For me, however, the most striking thing about the Monastery was the amazingly harmonious integration of a man-made structure into the surrounding nature.

Several restaurants line the shores of the turbulent Buna river. If you are hungry, definitely take your time and devour good food, fresh river air and an incredible view.

After visiting the Monastery, most tourists leave and go to their next destination, which – in my view – is a great mistake. My recommendation is: explore the village of Blagaj. Not for the sake of particular attractions, but simply for immersing yourself in its narrow streets and checking out old (some inhabited and some abandoned) houses.

One more thing to do before leaving Blagaj is to have a cup of coffee (or glass of wine) in one of the local bars. The chances are great that you will be the only stranger sitting there with the locals. The regulars are mostly elderly men who sit there for hours, sip their drinks, and discuss whatever needs to be discussed. It feels like touching the daily life of a village.

I left Blagaj in the late afternoon. The next planned adventure was exploring Bosnian wines and the best preserved walled town in Bosnia.

Best Wines and Most Beautiful Walled Town of Bosnia

In the introductory section (click HERE), I wrote about some mouthwatering Bosnian foods and dishes. Now is the time to reveal one more fact which would be interesting for genuine “Epicureans:” Bosnia & Herzegovina makes good wine. Most of the production is concentrated in the southern and southeastern parts of the country: around the cities of Citluk and Trebinje. I planned to visit both and check out a few wineries.

The first destination was the Rubis winery. Before the trip, I knew little about winemaking traditions in Bosnia, and so, this first visit was also a somewhat educational opportunity. Founded in 2014, Rubis has already achieved a certain fame for both the wide variety and quality of its wines. I arrived a few minutes earlier than agreed and wandered around. The winery looked brand new and built using traditional Bosnian technology. Its walls were made from the solid stones cemented with a lime-based mortar.

Perfectly on time, the owner of the winery, Oliver Mandaric, arrived and invited me inside. An impressive selection of wines was awaiting in the tasting room and – a cherry on top of a cake – the plate with local olives, sausages and cheeses.

Oliver gave me a crash-course on Bosnian wines and explained that besides grapes which can be found elsewhere (like Cabernet, Merlot, and Chardonnay), two grapes varietals have been grown in Bosnia for centuries and are truly unique to this country.

One is Zilavka which is used to make fresh and aromatic white wines with crisp acidity and minerality. Think about citrus fruits (lemon, grapefruit) or white peaches – this is how the flavors of Zilavka wines are usually described.

The other, a red, varietal native to Bosnia & Herzegovina is Blatina. It is a grape which thrives in the Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers, and mild winters. Blatina wines are robust and full-bodied but with soft tannins and balanced acidity making them both complex and yet easy-to-drink. When I tasted Oliver’s Blatina, I was literally “immersed” in the aromas and flavors of dark fruits (blackcurrants, blackberries, cherries) accompanied by peppery spice.

A curious fact about Blatina grapes is that they have functionally “female” flowers: this means Blatina cannot self-pollinate. In order to bear fruit, Blatina vines must be planted side-by-side with other grape varietals that serve as “male” pollinators. This dependency on cross-pollination can be a challenge: if weather conditions are poor during the flowering period (like rain), then there will be no grapes.

Oliver shared many other interesting facts about Bosnian wines, while constantly filling my glass with new samples from the various bottles lined up on the table.

Besides Zilavka and Blatina, I also bought a white wine with a strong Muscat aroma. It was made from Tamyanka grapes which are named after tamjan (“frankincense”), due to the intense scent from the ripe grapes, which can be detected several meters away.

One of the walls in the tasting room was decorated with a huge painting: it was a portrait of a gentleman standing in front of grapevines with a coffee mug in his hands. Oliver told me that this was his late uncle. He had a dream of having winery and was getting ready to accomplish this plan.

Regrettably he died from cancer, but in his will he bequeathed to Oliver a significant amount of money and a request to fulfill his dream. Oliver had other life plans, but he admired his uncle and also loved trying new things. And so the Rubis winery came into existence.

Bottom line: if you like good wines and good stories, the Rubis winery is a great place to visit: https://rubis.ba/en/prica

This night I was staying in the town of Capljina (about 20 minutes from Rubis winery). The owner of the guesthouse gave me a “secret tip:” to visit the brand new not yet open to the public, but very promising winery “Vino Matic.” It was already after 6 pm, but I called anyway, and Antonio Matic (the son of the founder) said: “No problem, come over, I am waiting for you.” The winery and tasting room were right in the middle of Capljina.

Antonio greeted me with a big smile and said: “I have a party to go in about one hour, but I am glad that you are here. Let’s have some wine.”

Compared to Rubis, Vino Matic is much smaller: both in overall production and variety of wines. But then, it has a nice feel of a truly family-run winery, and the two wines I tasted were both “five stars” quality. The first was Zilavka, and, frankly, it was the best Zilavka of all I had in Bosnia.

The second, a red wine, was made from Trnjak grapes. Historically, Trnjak was planted alongside and used to pollinate the “female” Blatina vines. However, no wines were produced from Trnjak on its own due to relatively low yields. Things changed recently, when Trnjak gained recognition as a varietal showcasing unique and appealing characteristics.

The Trnjak from Matic was excellent: full-bodied and with a complex flavor. Each sip was like an explosion of many different berry notes: blackcurrant, raspberry, cherry, and plum jam – somehow they all complemented each other nicely.

I bought both wines and thanked Antonio for the opportunity to “preview” his winery and tasting room. Here is the website of Vino Matic: https://www.vino-matic.com/

Besides wineries, there was another reason to visit this area: I wanted to see Pocitelj, reportedly the best preserved and most picturesque walled town in Bosnia & Herzegovina. Generally, when traveling in Bosnia, it feels that nearly each town has a fortress which typically sits on a hill, above the settlement.

And yet Pocitelj is unique, because the whole town is like a fortress carved into the side of a steep karst cliff overlooking the Neretva River. Predictably, it is a popular tourist destination, and, therefore, the best time to explore is early morning, before the throngs of visitors would come. I arrived at around 7 am and entered the town through the wide stone staircase.

The morning was perfect with bright sun, fresh air, and a polyphony of chirping birds. As I walked the streets of Pocitelj, I noted many wild flowers that had managed to proliferate through the rocks and solid stones.

Founded in the late 14th century, Počitelj was conquered and changed hands several times. But one way or other, until the late 19th century, it held major strategic importance as a fortress which controlled the passage along the Neretva River, a vital trade and military route.

As time went by, Pocitelj continued to grow and evolve. Its various rulers (Bosnian Kings, Ottomans, Austro Hungarians) each added something to the appearance of the town. Today, the town meets visitors with a blend of medieval and late Ottoman architecture featuring stone houses with hipped roofs, narrow cobbled streets, and various public buildings.

And here is a word of warning for those who visit Pocitelj. Its winding streets and trails are like a haphazard cobweb, where one can easily get lost. The good news is that it is a small place, and eventually you will find your way around.

In my case, after going astray, I was rewarded by stumbling upon an amazing observation point. From here, I could clearly see the valley carved by the Neretva River and the entire gigantic karst amphitheater where Pocitelj was nestled.

I stayed at this viewpoint for a while, and then realized that the streets of the town were beginning to fill with people. The locals put out their stands with souvenirs, snacks and drinks, while the first wave of tourists began their daily conquest of Pocitelj. It was time to leave and head to the next destination, the Kravice Waterfall.

The landscapes of Bosnia & Herzegovina are in many ways defined by water: lakes, rivers and streams are everywhere. Not surprisingly, this small country has a decent share of beautiful waterfalls. And if you were hard pressed to choose ONLY ONE for a visit, then it should be Kravice Waterfall.

Situated only 30 minutes away from Pocitelj, it is actually not a single waterfall, but a stunning amphitheater of cascading water tumbling over green tufa deposits and into emerald green lake at the base of the falls .

Predictably, Kravice Waterfall is an extremely popular tourist destination, and the whole place feels fairly commercial: there is a designated parking lot, entrance fee, and hours when one can visit. But it is magnificent anyway, and – surprisingly – it is Okay to swim in the lake right under the waterfalls.

I had a quick picnic lunch devouring both the food and the gorgeous view. In the afternoon, I drove to the next destination: the town of Trebinje which would become my favorite town in Bosnia & Herzegovina.

My Favorite Town: Trebinje

When traveling, people sometimes immediately connect to certain places, feeling welcomed and ‘at home’ right away. This happened to me in Trebinje, a town only 40 minutes away from the major tourist destination on the Adriatic coast, the city of Dubrovnik in Croatia.

Stretched along the Trebišnjica River and nick-named “city of the sun,” Trebinje offers a pleasant blend of history, culture and natural beauty. It charms visitors with its picturesque Old Town, graceful bridges, shadowy sycamore trees, and relaxed laid-back atmosphere. Trebinje is also a center of a burgeoning wine region, and as such it definitely has money: the town looks clean and well-kept.

I arrived in Trebinje in the early evening. My accommodation was in “Apartment Crkvina,” and, hands down, it was another great find. Located on the slope of a hill, with a view over Trebinje, the “apartment” was actually a small cottage, with a private garage, and a big balcony.

Daliborka, the owner of “Crkvina,” and her cute “co-host,” poodle Mona, were waiting and helped me settle in the cottage. Fast forward, during two days in Trebinje, I felt as if “Crkvina” was designed not for transient visitors, but for the owners themselves: everything was comfortable and very well thought-out. If you decide to stay at “Crkvina,” either look on Booking.com or get in touch with Daliborka via WhatsApp: +387-66-879-141

From “Crkvina,” in the approaching twilight, I walked along the winding road which was ascending to one of the major local attractions, the “Hercegovacka Gracanica Temple.” Set on the top of a hill and with far-reaching views over the surrounding valleys, Hercegovacka Gracanica is a Serbian Orthodox Monastery. It was built in 2000 as a replica of the famous 14th century Gracanica Monastery in Kosovo.

For the Serbian people, the original Gracanica Monastery is associated with the power and aspirations of the medieval Serbia. And it is also a symbol of the enduring spirit and resilience of Serbs and their Orthodox faith through turbulent times.

I have never been to the original Gracanica, but its copy in Trebinje was impressive: especially, the imposing Byzantine-style main church with its colorful frescoes and gilded altar.

Predictably, for Serbs living in Bosnia & Herzegovina (they comprise 31% of the population), Hercegovacka Gracanica is a pilgrimage destination. Besides the main church and bell tower, the monastery complex includes a guesthouse, several shops, and a restaurant. There is also an outdoor cafe which sits right at the edge of the cliff offering panoramic views of Trebinje.

I sat down in the café and ordered dinner, as a lovely sunset unfolded over Trebinje.

The next morning, I headed down the hill and across the Trebisnjica river to explore the Old Town.

The heart of Trebinje is “Pijaca” (“Market”) with an adjacent shadowy square and the hotel “Platani” (“Sycamore”).

By the way, Sycamore trees are considered a symbol of Trebinje, and there is a story related to this fact. At the end of the 19th century, under Austro-Hungarian rule, the central administration in Sarajevo decided to give Trebinje a more modern look and developed an entirely new urban plan.

Among other things, 20 Sycamore tree seedlings were planted in the city center in the shape of a rectangle giving birth to the current square. In 1941, the hotel “Platani” was added. Remarkably, out of 20 original trees, 16 are still alive. Overall, the center of Trebinje has a very “green” feel, and I spent a good chunk of time simply strolling in the shade of the century-old giants.

Walking in Trebinje, you will also discover many sculptures and monuments related to various historic personalities and events. Even without knowing “who or what is this about,” it is simply pleasant to see these fairly elaborate pieces of art.

One of these monuments is dedicated to very recent events: the Civil War of 1991-95 (I wrote about it HERE in introductory section). Called “Monument to the Defenders of Trebinje,” it is essentially a memorial for all who died during the brutal conflict which took the lives of 100,000 inhabitants of Bosnia & Herzegovina.

To put this number in perspective, considering the country’s total population, it would be equal to more than 10 million Americans if US would experience something like the events of 1991-95 in Bosnia & Herzegovina.

It appears also that the people’s memory of the 1991-95 events is still pretty much alive. In many places in Trebinje, I saw wall murals dedicated to the victims of the Civil War.

Besides the Sycamore-lined square, “Pijaca” (“Market”) is another important component of the Old Town’s center. And indeed, every day “Pijaca” functions as an open-air market, with many vendors selling local products of all kinds: plants and flowers, various foods and handicrafts.

Look for example at this stall which has literally everything a person may need: various cheeses and meats, olive oil and different preserves, herbs and grains, home-made wine and “rakija” (a traditional Bosnian strong liquor).

Nice thing about shopping at Pijaca is that you can sample almost all the food items. I particularly liked the goat and cow milk cheeses sold by this cheerful lady, and got from her all supplies for both lunch and dinner.

The only missing items were bread and “pitas” (Bosnian pies with different savory fillings). Walking back to “Crkvina” apartments and very close to Pijaca, I found a bakery called “Pekara Leotar.” It did not disappoint: both the “pitas” and the poppyseed pastries which I bought were excellent.

Back at “Apartment Crkvina,” I prepared a picnic-style lunch which consisted exclusively of locally made products.

Trebinje is one of the major wine-producing centers in Bosnia & Herzegovina, and it is surrounded by dozens of vineyards. Most of them offer tours and wine-tasting, and my choice fell on the “Bojanic” winery. From the online reviews, it appeared to be a place with good and diverse wines and hospitable owners. One customer even described it as “a hotspot of Bosnian wines and hospitality.”

“Bojanic” is only about 4.5 km / 3 miles from Crkvina Apartment, and I decided to walk there. The route turned out to be quite scenic. The first part was along the shadowy embankment of the Trebisnjica river.

And then, the city streets evolved into country roads with views of vineyards and wild flowers.

Stevo Bojanic, the owner and winemaker at the “Bojanic” winery, suggested that we meet in the garden at his private house.

The Bojanic family began commercial wine making three generations ago, but with only 2 hectares / 4 acres of vineyards and 30,000 bottles produced annually, it remains small and truly family-run winery. All Stevo’s wines are sold locally, with “demand” actually exceeding “supply.” I asked “Given your popularity, why don’t you expand the winery and production?” Stevo’s answer was: “I want to keep it the way it always was and is now, when everything is done within the family.”

Then Stevo walked back to the house to bring his wines to taste, while I was waiting in the company of the “winery-cat” named Garfield.

I tasted several Bojanic wines, and they all were good and memorable. Yet, one – in my opinion – was truly outstanding: the red wine made out of Vranac grapes which originate from Montenegro but are now common in many Balkan countries. Stevo’s Vranac was fresh and young, but, at the same time, full-bodied and bursting with aromas of black cherries and chocolate.

Besides wine, Stevo’s family has another tourist-oriented business. Upon request, they offer lunches and dinners made exclusively from local products, accompanied by Bojanic wines and served in their garden.

This was not planned, but Stevo brought a generous plate with various cheeses, condiments and cold cuts, insisting that tasting good wines is senseless without equally tasty munchies. Clearly, my original image of Bojanic hospitality matched reality 100%.

If you decide to visit “Bojanic,” get in touch with Stevo via WhatsApp: +387-65-987-462

I bought several bottles of Bojanic’s Vranac, and walked back to the town. There was just enough daylight left to see another major attraction of Trebinje, the Arslanagic Bridge which is recognized as the National Monument of Bosnia & Herzegovina. It was built in 1574 by Mehmed Pasha Sokolović, a Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, as a tribute to his son who was killed in battle against the Venetians.

Due to its impressive design with distinctive double-backed structure and elegant shape, the Arslanagic Bridge is considered the most important architectural monument from the Ottoman period in Trebinje

When waiting for sunset at the Arslanagic bridge, I was kicking myself for booking only two nights in Trebinje. It turned out to be a lovely place, and I had seen only a fraction of what this town can offer. But another adventure already awaited the next day: hiking in the Sutjeska National Park which is situated on the border between Bosnia and Montenegro.

Mountains, Glacial Lakes and Wild Horses: Sutejska National Park

Bosnia & Herzegovina is small: it is comparable in area to the US state of West Virginia. And yet this country has an impressive natural diversity, and it is home to four national parks: each offering unique landscapes and wildlife. The most important and oldest is Sutejska National Park which extends into neighboring Montenegro. Here is the Parks’s official website: https://sutjeskanp.com/

The Sutjeska Park has many highlights. These include Maglic, the highest peak in the country (2,386 m / 7,000 feet); Perućica primeval forest (dating 20,000 years back, it is one of the last remaining primeval forests in Europe); the Sutjeska River canyon, and the scenic Zelengora mountain with its glacial lakes (often called “mountain eyes”).

The challenge was that my trip to Bosnia was short, and I had only one day to literally “take a look” at Sutjeska Park. Luckily, I found an excellent website (HERE) created by a fellow-traveler who meticulously described all possible destinations and itineraries for Sutjeska. It helped greatly to make plans for the visit.

First, I drove to the information center in Tjentiste. A curious fact is that Sutjeska Park was established originally (1962) not as a nature conservation area, but as the memorial of the WWII Battle of the Sutjeska. Back in 1943, the vastly outnumbered Yugoslavian partisans foiled the plans of German occupying forces and broke out of their massive encirclement. An impressive monument commemorates this event at the northern edge of the Park and right next to the information center.

The information center turned out to be more like a small gift shop run by an elderly lady (not a park ranger of any kind) who spoke neither English nor German. Thanks to “Google Translate,” I was able to get directions to the trailhead leading to my destination, Trnovacko Lake.

It took almost one hour to drive 18 km / 12 miles to “Prijevor,” the parking lot for the trailhead. The winding forest road was bumpy and with many potholes: speeding up was definitely not a good idea. But when I finally arrived, the wide-open views over dark-green plateaus and distant snow-covered mountains fully compensated me for all the inconveniences.

In the distance, I noted something like an observation tower and walked there before setting off for the hike. Indeed, it was an observation tower which offered even better views of the area.

And then I set off to Trnovacko Lake, reportedly one of the most charming mountain lakes in the Balkans. The trail was well marked, and the hike was only about 6 km / 4 miles. In terms of difficulty, I would call it “medium strenuous:” count on 2-3 hours each way.

From Prijevor (elevation 1670 meters / 5470 feet), the trail first climbs to the mountain pass, Prevoj Trnovacko vrata (1750 meters / 5740 feet). At the beginning of the trail, I saw some abandoned houses: perhaps, these were the remains of shepherds’ huts from the times before the National Park was established?

And then the last signs of human presence disappeared. Only majestic wilderness was around, as I continued to hike along the rocky scree.

After Prevoj Trnovacko Vrata, the hike continues first through dense forest and then enters lush meadows which are real “delight for the eyes.”

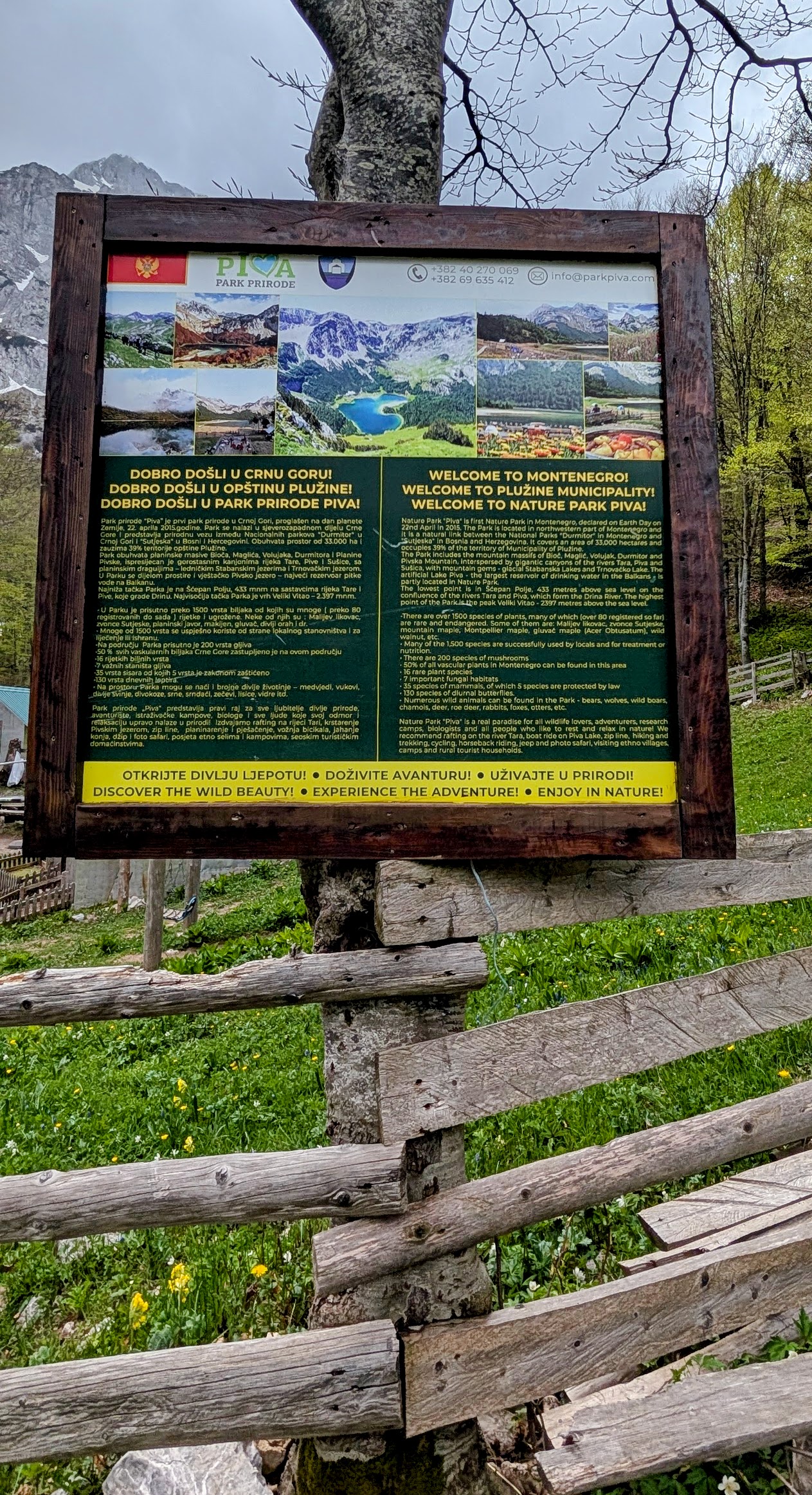

After these meadows, there is again a slight ascent, and finally Trnovacko Lake (elevation of about 1500 meters / 4700 feet) comes into view. But before reaching it, you will need to cross the border between Bosnia and Montenegro. Yes, the Lake is actually on the Montenegro side of the Park.

There is no border guards or passport control of any kind: only a sizeable billboard greets and welcomes visitors to Montenegro.

Formed by retreating glaciers about 25,000 years ago, Trnovacko Lake is about 800 meters / 2500 feet long and 400-715 meters / 1200-2200 feet wide (depending on which part is measured), with a maximum depth around 9 meters / 30 feet.

Besides other things, Trnovacko Lake is also known for its heart-like shape. However, in order to fully appreciate the view, one needs to climb to the top of one of the surrounding mountains. When I entered the valley nestling the lake, the weather was gloomy: grey skies and a light drizzle did not feel like a real “welcome!”

But then, the sun broke through the clouds, and I saw the lake exactly as it was described by other travelers: with emerald-green waters reflecting the towering mountains. The Maglic Peak, the highest Bosnian mountain was prominently visible in the distance.

The view was stunning. With formidable limestone cliffs all around, I felt like being in the middle of a giant natural glacial cirque and amphitheater.

There were two cabins on the other side of the lake. I walked there, but they were locked. As I learned later, one of them was used by the park rangers, while the other can be reserved by those who wish to spend the night at the lake.

This is a great option for people who want to hike from Trnovacko Lake to the summit of Maglic Peak. The ascent there takes 3 to 3.5 hours, and spending a night at the Lake either before or after the hike makes the experience much more pleasant and relaxed.

I stayed at the lake for about one hour. It was early May, and the wild flowers were in the full bloom.

And then I headed back to Prijevor. Surprisingly, the return hike was actually easier and faster than I expected. Perhaps, I was “charged” by the natural energy of the lake and the mountains?

As I was nearing the parking lot, a pack of gracious horses appeared and passed by on the trail. These were feral horses, and they looked like the real owners of this otherwise deserted area.

I left Sutejska National Park in the late afternoon and drove (4 hours) to Travnik, the town which served as the capital of Bosnia in the times of the Ottoman Empire.

Once the Capital of Bosnia: Travnik

In the mid-15th century, Bosnia was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. With the new rulers came new religion (Islam) and many other cultural influences that would shape the region for centuries.

Before that, in the times of the medieval Bosnian Kingdom, Jajce had proudly stood as the capital town, but the Ottomans shifted the administrative heart of Bosnia to Travnik. The latter became a vibrant cultural center and the seat of power for the “Viziers,” the highest-ranking officials appointed by the Ottomans to govern Bosnia.

When I planned trip to Travnik, besides the desire to see the vestiges of Ottoman-era Bosnia, another draw was the abundance of hiking trails in the Vlašić mountains surrounding the town.

The Vlašić mountains are also famous for cattle breeding, and the production of Vlašić cheese, a local delicacy. It is made primarily from sheep’s milk and then matured in brine for 2-3 months. The result is a soft cheese, with small holes, and a lightly sour-salty taste. Its distinct acidic flavor comes from the local mountain herbs grazed by the animals.

About 18 km / 12 miles from Travnik, there is a cheese farm called “Sir iz Kace.” Its name translates to “cheese from a wooden barrel” and refers to a traditional method of making cheese, when it is aged and stored in a “kaca,” a wooden vat or barrel, filled with brine (salted water).

Inside the farm shop – which also looked like a cheese-barrel – I found a nice lady, the owner of the farm. Besides Vlasic cheese, she also offered a variety of smoked cheeses, which are apparently very popular among the locals. And what was really nice, the farm had a vacuum-packing equipment, not a very common feature in Bosnia’s small shops.

The cheese was excellent, and I ended up buying a few pounds to take back home to California. Clearly, “Sir iz Kace” is not the only place to get Vlasic cheese in Travnik. The town has a vibrant daily open-air market.

To my cheese supply, I added vegetables and fruits (strawberries were in season!) and also some smoked meats. Not surprisingly, with its thriving cattle industry, Travnik offers a good selection of high quality meat products.

Sheep-cheese production in Travnik has a “secondary” outcome. Local farmers use the lamb wool to make socks and slippers. Thick and warm, they are also richly ornamented making a great (and easy-to-transport) present to take back home. Look at the picture below: a pair of these excellent wool slippers costs only about US$ 6

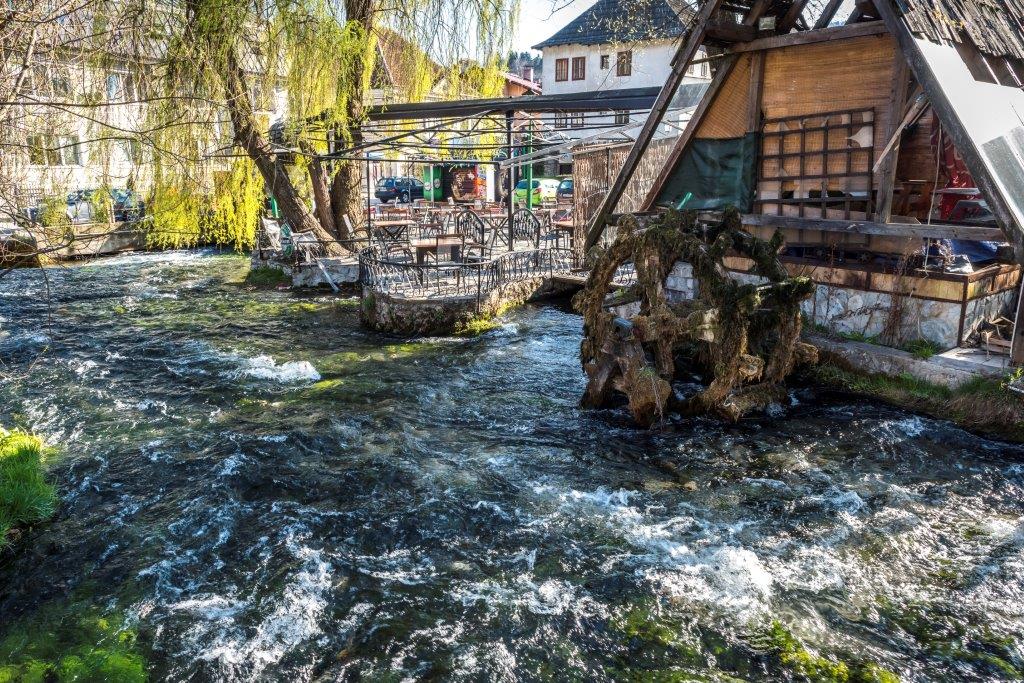

In the afternoon, I walked to the Plava Voda (“Blue Water”), a spring which emerges from a split at the foothills of the Vlasic mountains and creates a mighty stream passing furiously through the Old Town of Travnik.

In the past, Plava Voda served as a water supply for the city and a source of energy for watermills. The latter were used to beat the oak bark needed for tanning leather in Travnik’s many tanneries. Today, the scenic area around Plava Voda is surrounded by many cafes one of which (Lutvina Kahva) dates back to the 19th century.

Recharged with strong Bosnian coffee at Lutvina Kahva, I walked to the Travnik fortress which is arguably one of the best preserved fortifications in the country dating back to the medieval Bosnia, to the era before the Ottoman Empire.

Built initially as a castle, it was then expanded by the Ottomans into a real fortress with many buildings inside its walls, effectively becoming a “town within the town.”

The fortress is located on the eastern side of the present-day city and on a steep rocky slope. From its walls, I could see the entire Travnik sandwiched between two mountain ranges.

The Old Town of Travnik, however, lies immediately at the foot of the fortress and to the south of it. Looking at the many minarets appearing in this direction, I tried to picture the everyday life her under the Ottoman Empire.

Look at the building marked with a red cross: today, it is Travnik’s best hotel “Vezir Palace.” But back then it was the site of the actual Vezir Palace, the home of Bosnia’s Ottoman rulers.

I walked around Travnik for a couple of hours and then returned to my rental apartment. For dinner, I fixed a plate with all the goodies I had acquired today at “Sir iz Kace” and the city market.

The next day was set aside for hiking in the Vlasic Mountains, but the plan didn’t go as envisioned. For my starting point, I chose the place marked on Google maps as “Ljuljacka Galica, Vlasic.” It was about 18 km / 12 miles from Travnik and apparently served as the hub of many intersecting trails.

When I left Travnik, the town was basking in sunshine. But gradually ascending into the mountains, my car eventually hit the clouds. By the time I arrived at “Ljuljacka Galica,” everything was covered in thick and wet fog. Yes, there were many signs indicating all possible trails, but under such conditions hiking did not make any sense.

I looked at Google maps searching for some alternative at the lower elevation and found a place called “Snijezna Gospa” which means “Snow Maiden.” Apparently, it was a Roman Catholic Chapel but in a somewhat unusual location: far away from any settlements. I drove there, eventually coming back to more suitable weather conditions and then reaching the point where a wooden sign indicated the trail to the chapel.

The hike was very short (only about 20 minutes), and the chapel looked cute and well-maintained. It was also a nice spring day and it felt like the forest surrounding “Sniezna Gospa” was finally awakening from the long winter.

Then I realized that the trail continued beyond the chapel and followed it. In about 5 minutes, I reached a plateau with several tables, massive benches, and a gazebo.

I walked to the edge of the plateau, and it was one of those “Wow moments:” the far-reaching view over the valley and Travnik was simply incredible. Later, I was able to locate this observation point on Google maps: it was called “Vidikovac Vukovica Brdo.”

Well, the day did not go as planned, but there were definitely no regrets on my part. I had a picnic lunch and stayed for couple of hours sunbathing and enjoying the view.

After return to Travnik, in the approaching twilight, I walked to the place which was intentionally “reserved” for the last evening, the Ornamented Mosque. This is the most visually striking landmark of Travnik going back to the times of the Ottoman Empire.

The mosque was originally erected in the late 16th century, but the current appearance dates to around 1815-1816. It is famous for the frescoed facade with intricate floral patterns, a rare sight in Bosnian mosque architecture. Colorful depictions of trees, grapevines, and poppies, along with Arabic calligraphy – all these make the Ornamented Mosque a standout and very appealing piece of artistry.

With vibrant colorful paintings and elaborate wood carvings, the interior of the Ornamented Mosque is equally impressive.

Another rather unique feature of the Ornamented Mosque is that its ground floor has always housed a “bazaar” with with various shops (now also a cafe). This blend of sacred and secular functions within the same building is also quite rare in Islamic architecture.

I left the Mosque and walked back to the apartment. The next-day destination was another former capital of Bosnia, the town of Jajce which used to be the center of the medieval Bosnian Kingdom.

It Is All About Water: Jajce

Before its absorption into the Ottoman Empire in the mid 15th century, Bosnia was an independent state, the Kingdom of Bosnia. At its zenith, the borders of the Kingdom extended into areas that are parts of present-day Croatia, Montenegro, and Serbia. Back then, the town of Jajce was the capital of medieval Bosnia.

Jajce witnessed both the rise and the fall of the Bosnian Kingdom. The last Bosnian King, Stephen Tomašević, was executed here by the Ottoman conquerors in 1463.

Jajce is also considered the birthplace of the post-WW II Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) met here in November 1943 and discussed the foundation for the new Yugoslavian state. But history aside, Jajce offers many other worthwhile attractions.

Approaching Jajce by Hwy M16, on the right side of the road, I saw the sign “Pita Ispod Saca Kod Hamde.” In the introductory section (click HERE), I wrote about “pitas” (Bosnian traditional savory pies) and about “iz pod saca” being an ancient method of making them.

A good number of cars were parked at the pita shop, and, following the crowd, I stopped as well and had a scrumptious breakfast consisting of straight from the oven “zeljanica” (pita with spinach) and “baklava” (layered cake with nuts and honey). By that time, I had already tried many “pitas,” and could tell that this one was of top-notch quality.

After Kod Hamde, in a few minutes, Jajce came into view. The town sits at the confluence of the Vrbas and Pliva rivers, with Hwy M16 winding along the Vrbas and offering excellent views of the Jajce skyline.

My accommodation, “Apartment Mima” (found it on Booking.com), was right next to the old fortress overlooking Jajce. As it turned out, getting there by car through the narrow cobblestone streets was a bit tricky. Using Google maps, I “dead-ended” in front of a medieval tower. It had gates, but they were too narrow to drive through.

I called my host, Mima, and she came to my rescue explaining that it was totally Okay to leave the car here and simply walk to the house which was only about 50 meters / 150 feet behind the gates.

The “Apartment Mima” was as lovely as Mima herself, but its best selling point was its location: by the the walls of the fortress and with a commanding view of Jajce.

After settling into Mima’s house, I walked (about 2 minutes) to the fortress. Built in the 13th century, it was not just a defensive structure, but also the seat of Bosnian Kings. In 1461, the fortress witnessed the coronation of the last King of Bosnia, Stephen Tomašević, and, just two years later, it became his initial burial site after the King’s execution by the Ottomans (later, his remains were moved to the Franciscan Monastery).

A small statue inside the fortress commemorates the last Monarch of the medieval Kingdom of Bosnia.

What adds to the fame of the Jajce fortress is that it remained the last stronghold of Bosnia’s resistance to and independence from the Ottomans even after the King’s execution. Indeed, in the same year (1463), Jajce was recaptured from the Ottomans by the Hungarian King Matthias. He established the “Banovina of Jajce,” a Hungarian-controlled territory that acted as a buffer state, holding off the Ottomans for another 64 years until Jajce finally fell in 1527.

Both Bosnian Kingdom and Ottoman Empire are long gone, but the Fortress still sits majestically on the top of a pyramidal-shaped hill and presents curious visitors with sweeping views of Jajce and its surroundings.

Jajce actually witnessed a much earlier human civilization than the Medieval Bosnian Kingdom. In the times of the Roman Empire, this area was part of the Dalmatia province. One of the main local attractions is the “Mithraeum,” a temple dedicated to the Persian god Mithra.

In the Roman Empire, the cult of Mithras, a god of light and truth, was particularly popular among soldiers and merchants. Dating back to the 2nd-4th centuries AD, the Mithraeum is one of the best-preserved Mithraic temples in the entire Europe.

After exploring the Jajce Fortress and Mithraeum, I had enough of history. It was time for something more “alive.” Remember, I called this chapter “It Is All About Water” and, indeed, there are several good reasons for doing so.

The first is the Pliva Waterfall, Jajce’s most iconic landmark. It is right in the heart of the town, where the Pliva River cascades into the Vrbas River. Being about 20 meters / 65 feet high and 40 meters / 130 feet wide, the Pliva Waterfall is not particularly big. Yet, being right in the city center, it creates a rather stunning setting.

The second water-related attraction is about 6 km / 4 mi out of town. These are “Mlincici,” a collection of small, old wooden watermills situated on a travertine barrier between the Great and Small Pliva Lakes. The 400 years old watermills were used for grinding grain, mostly corn and wheat.

Why are there so many of them in the same place? Because each was owned by a particular family of local farmers and shared only among immediate relatives.

I walked among them and felt like being in some fairy tale. All in all: Mlincici is a lovely and charming place.

And not only Mlincici, but the entire area around “Plivsko Jezero” (Pliva Lake) is very picturesque. I stayed here for a couple of hours, walked along the shore and simply enjoyed the scenery.

There is an interesting place at the lake called “Most Ljubavi” (Bridge of Love). It is indeed a narrow, wooden pedestrian bridge which intersects the lake along the top of a natural dam created by rock and stones.

On one side of the bridge, the lake is significantly higher than on the other. And so, walking on Most Ljubavi you will go over the top of many cascading waterfalls.

I liked Jajce and could have easily spent here 2-3 days. But my trip across Bosnia & Herzegovina was almost over and I had only one more day left.

Just a Nice “Normal” Town: Tesanj

The last day of my trip to Bosnia arrived and the plan for this day was somewhat unusual. I wanted to spend time in a “normal” (not popular among tourists) yet nice town. I played with Google Maps, clicked on the names of various villages and towns, and looked at their images and reviews left by other people.

Eventually, I found a good candidate: the town of Tesanj, in the north of Bosnia & Herzegovina and about 60 km / 40 miles from the border with Croatia. It was a bit far from Jajce (where I was previous day) and Sarajevo (where I needed to be tomorrow), but I drove to Tesanj anyway and did not regret this choice. The main town square looked nice and fairly alive with several cafes and restaurants.

I parked the car, walked into one of the cafes and ordered a traditional Bosnian coffee: it felt like the right way to begin my exploration of a “real” Bosnian town. The coffee was prepared and served nicely.

From the town square, a wide stone staircase climbed to the Tesanj fortress.

By that time, at the end of the trip, I had seen more than enough fortresses, an inevitable element of many Bosnian towns. But I figured that this would be the last one for me and – as always – it would offer the best views. And indeed, from the fortress, both the town and its surroundings looked very appealing.

It also turned out that the fortress was much larger and better restored than I expected. Further, it had a good museum with signs and explanations in several languages which is not very common in Bosnia.

I stayed in the fortress for awhile and then headed off to another local museum: “Eminagica Konak.” Essentially, it is a beautifully restored old house with several rooms featuring traditional furniture, decorations, dishes, tapestries, and much more.

The nice thing about Eminagica Konak was that – unlike most of museums of this kind – it was Okay to touch things, walk on the carpets (but I was given special slippers) or sit on the couches and benches.

I was the only visitor in the museum, and it was fun to simply wander around and imagine how it would be like to live here.

When I left Eminagica Konak, right next to it, I noted another big traditional house. It was abandoned and definitely needed a lot of repairs, but somehow it still had an elegant and even majestic look. I thought that this would be an excellent “restoration project” for someone who appreciates and likes to live in historic old homes.

For my last dinner in Bosnia, I had plenty of delicious food bought the previous day at the market in Jajce. One item, however, was missing: fresh bread. And here is a tip about one MUST VISIT place in Tesanj: the bakery “Pekara Saraj.” It offers only one kind of bread, but this bread holds a particular gastronomic and cultural significance in Bosnia. Called “somun,” it is a soft, light and round-shaped flat bread with a hollow inside.

With a slightly chewy crust, and a criss-cross pattern etched onto its surface, somun is always served alongside ćevapi (small sausages of minced meat), where it is used as the vessel for soaking up the savory juices. But in my view, freshly baked and hot somun is best enjoyed on its own.

During the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, the aroma of freshly baked somun wafting from bakeries is an integral part of the Ramadan experience. Families often purchase or bake this special bread to begin the iftar, the evening meal that breaks the daily fast.

As to Pekara Saraj in Tesanj, it is open 365 days a year (no exceptions!) from 9 am until midnight, but it does not have a store as such. Instead, there is a window and a bell which a customer rings, someone opens the window and sells the requested quantity of – always hot! – somuns.

The secret of authentic somun is in its simple yet precise preparation. The dough is made from a straightforward combination of flour, water, yeast, and salt. The key to achieving the airy crumb and soft crust lies in the short but very high-temperature baking in wood-fired ovens. This causes the bread to puff up, creating its signature hollow interior.

The somun from Saraj was so good that instead of leaving for Sarajevo early next morning, I waited until 9 am, because I wanted to buy more and also talk to the owner of the bakery. Well, when I came at exactly 9 am, a long line of other customers had already lined up on the street waiting for the opening. When my turn came, I ordered a few somuns, but – with other people waiting in line – it was impossible to chat. So, I asked only one question: “How many somuns do you bake and sell each year.” The baker replied: “I do not know, but usually couple of thousands each day.”

And so, the fresh hot somun for breakfast in the little “normal” town of Tesanj was my last cultural experience in Bosnia & Herzegovina. Altogether, I spent 12 days in this country, visited many places, stayed in seven different cities and towns, and talked with dozens of people. The most impressive thing about the entire trip was that looking back, I could not think of even one bad experience.

This small Balkan nation welcomed me and – let’s be honest – stunned with the richness and diversity of its nature and culture. Not surprisingly, when my plane was taking off from the Sarajevo airport, already made a plan for another visit. I will be back here for the famous Sarajevo international film festival (it is held each August) and there will be another story about this “most underappreciated” European country.

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Alexei,Congratulations on your trip! Fantastic views and dialogue.Stay well!+Nathaniel

LikeLike